Substance Abuse and Addiction-Related Word Associations

The editorial staff of Recovery.com is comprised of addiction content experts. Our editors and medical reviewers have over a decade of cumulative experience in medical content editing and have reviewed thousands of pages for accuracy and relevance.

The editorial staff of Recovery.com is comprised of addiction content experts. Our editors and medical reviewers have over a decade of cumulative experience in medical content editing and have reviewed thousands of pages for accuracy and relevance.

Table of Contents

Over time, the language we use to describe the world and communicate with one another has changed substantially. As “tweet” becomes an everyday word and “iPod” gradually supplants “CD,” certain terms go out of style while new words emerge from the latest ideas and concepts.

The evolution of language isn’t new—it’s been happening for thousands of years. So what does the history of language usage tell us about how the conversation around addiction and substance use has changed over time?

Like any other topic, alcohol and drug addiction have been shaped by major shifts in both cultural attitudes and scientific knowledge. Sumerians were writing about herbal medicines as early as 1700 B.C.1

Using the Corpus of Historical American English (COHA), compiled by Brigham Young University, we examined trends in how drugs and addiction have been discussed over the past 200 years.

The COHA collection contains 400 million words drawn from 115,000 textual sources, including spoken transcripts, spanning the years 1810 to 2009.2

How We Analyzed Language Around Addiction

We searched COHA for 14 common words related to substance use and addiction and charted their frequency since 1815.

To better understand context, we:

- Collected all words appearing within 10 words before and after each occurrence.

- Identified the most frequently appearing nearby words.

- Excluded common prepositions, pronouns, and conjunctions.

These surrounding words, referred to as the “most characteristic” terms in the graphs below, help illustrate how language and meaning have shifted over time.

“Addicted” and the Moral Lens of the 1800s

While many of the terms we studied peaked in the latter half of the 20th century, “addicted” got a strong start in the early 1800s.

During this era, the word was commonly paired with “habit” and used in condemnations of “vices,” “practices,” or “pursuits” viewed as morally suspect.

As alcohol use became a growing concern throughout the 1800s, terms like “intemperate” and “intemperance” appeared more frequently near “addicted,” reflecting the rise of anti-alcohol temperance societies.

Throughout this period, “addicted” also showed a strong association with “gambling.”

In the 1900s, the term increasingly became abbreviated to “addict,” and its usage reflected growing concern about the addictive properties of nicotine.

By the mid-1970s, mentions of “crack” near “addicted” skyrocketed alongside the crack cocaine epidemic.

As of 2009, “crack” was the most commonly used word appearing near “addicted.”

“Addiction” Enters the Modern Vocabulary

Unlike “addicted,” widespread usage of “addiction” appears relatively recently, peaking after the 1960s.

From that point forward:

- “Drug” dominates the surrounding language.

- “Heroin,” “narcotic,” and “narcotics” appear regularly.

- “Abuse” becomes increasingly common.

More recently, “sexual” appears more frequently alongside “addiction,” reflecting growing recognition of sex addiction. Notably, “crack” does not appear prominently here, suggesting phrases like “crack addicted” or “addicted to crack” were more common than “crack addiction.”

Alcohol, Alcoholic, and Alcoholism: Three Distinct Patterns

“Alcohol” as a Scientific and Regulatory Term

Mentions of “alcohol” have grown steadily from 1810 to the present. Until 1900, it was paired almost exclusively with “drugs.” As scientific literature expanded, new associations emerged:

- “Wood” alcohol.

- “Denatured” alcohol.

- Industrial uses involving “cellulose” and “shellac.”

Unexpectedly, words like “expressions,” “harsh,” and “scenes” also appear due to film guides published by the Christian Science Monitor, which reviewed movies for potentially problematic content—including alcohol use.

“Alcoholic” and the Substance Itself

In contrast, “alcoholic” has remained closely tied to consumption. In the 1800s, it appeared alongside:

- “Drink” and “drinks.”

- “Liquors”

By 1900, terms such as “beverage,” “beer,” and “beverages” became common, and most of these associations, including references to alcoholic “content,” have persisted to the present day.

“Alcoholism” and Medicalization

“Alcoholism” entered the lexicon around 1900, initially linked to “crime” and “dreams,” coinciding with the publication of Sigmund Freud’s The Interpretation of Dreams.

This soon shifted toward concern over:

- “Chronic” alcoholism.

- “Death” and “deaths.”

These associations peaked in the 1920s during the height of the prohibition movement. Fortunately, “dysgenic” (a term tied to discredited eugenics theories) quickly faded.

By the 21st century, alcoholism is most often discussed in terms of “abuse,” “addiction,” and “disease.”

Cocaine, Drugs, and Illicit Substances

Cocaine’s Late Arrival

Unlike many other terms, “cocaine” rarely appeared until the 1970s. Earlier mentions focused on its medical use as an anesthetic, leading to associations with:

- “Insensitive” (referring to numbness).

- “Morphine” and “heroin.”

- “Opposition” from critics who viewed it as dangerous.

As cocaine became more prevalent, discussions shifted toward those who “sniff” the drug and dealers who “push” it. At its peak, cocaine was most often discussed alongside “drug,” “heroin,” and “marijuana.”

The Rise of “Drugs”

The term “drugs” was used sparingly before 1950, then skyrocketed to become the most commonly used word in our analysis.

Historically, it referred to imported goods like “food,” “medicine,” and “spices.” Medical associations followed, including “chemists,” “curative,” and “quinine.”

By the 21st century, “drugs” most often appears alongside “drug” and “alcohol,” grouping them together as substances of abuse and addiction.

Heroin, Marijuana, and Narcotics

“Heroin” does not appear frequently enough for analysis until after 1900. Early on, it was discussed alongside “morphine” and “cocaine,” and already linked to “addicts.”

By the mid-1900s, heroin frequently appeared near:

- “Addiction.”

- “Marijuana.”

- “Methadone” and “clinics,” reflecting the rise of methadone maintenance therapy.

“Marijuana” enters the record in the 1940s, during efforts to ban cannabis in the U.S. It was often mentioned with “heroin,” “opium,” and “cocaine,” and briefly labeled a “narcotic.” As of 2009, it commonly appeared near “alcohol,” “drug,” and “drugs.”

Meanwhile, “narcotics” shifted from naming specific substances in the 1800s to taking on a bureaucratic tone in the 1900s, appearing alongside “police,” “indictments,” and “bureau.”

Intoxication, Overdose, and Opium

“Intoxicated” peaked in the 1800s and has since declined by more than two-thirds. Early usage referred both to being intoxicated by “liquor” and metaphorically intoxicated by “beauty.” Over time, it became associated with crime, jail, and eventually intoxicated “drivers.”

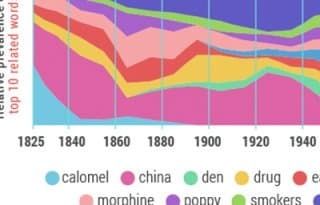

“Opium” peaked in the 1800s and again in the late 1900s. Early associations include “calomel” and “eater,” the latter popularized by Thomas De Quincey’s Confessions of an English Opium-Eater. Interestingly, references to opium “dens” increased throughout the 1900s, likely due to historical fiction.

Because “overdose” appeared infrequently, we combined “overdose,” “overdosed,” and “overdoses” for analysis. Early usage was medical, tied to “doctor” and “accidental.” Later associations included “sleeping pills,” “insulin,” and eventually, death from a “drug.”

Find Treatment Centers With Recovery.com

Understanding addiction starts with language, but healing starts with action. If you or someone you love is struggling, Recovery.com makes it easier to find drug and alcohol treatment centers that fit your needs. Explore trusted rehab options, compare programs, and take the next step toward recovery.

-

https://books.google.com/books?id=Cb6BOkj9fK4C&pg=PA12&lpg=PA12&dq=sumerian+cuneiform+opium#v=onepage&q=sumerian%20cuneiform%20opium&f=false

-

http://corpus.byu.edu/coha/. https://www.english-corpora.org/coha/

Our Promise

How Is Recovery.com Different?

We believe everyone deserves access to accurate, unbiased information about mental health and recovery. That’s why we have a comprehensive set of treatment providers and don't charge for inclusion. Any center that meets our criteria can list for free. We do not and have never accepted fees for referring someone to a particular center. Providers who advertise with us must be verified by our Research Team and we clearly mark their status as advertisers.

Our goal is to help you choose the best path for your recovery. That begins with information you can trust.