Exposure and Response Prevention Therapy: Insights for Family Reunification and Restoring Connection

Dr. Mala, is the Chief Clinical Officer at Recovery.com, where she develops impartial and informative resources for people seeking addiction and mental health treatment.

Dr. Mala, is the Chief Clinical Officer at Recovery.com, where she develops impartial and informative resources for people seeking addiction and mental health treatment.

In mental health care, we often treat interventions like compartments—one tool for anxiety, another for trauma, another for family systems. But healing rarely lives in silos. It moves in circles, overlaps, and reemerges across seemingly unrelated landscapes.

This is especially true when it comes to exposure and response prevention (ERP) therapy, long considered the gold standard treatment for obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).1

When we step back, we begin to see how foundational ERP principles—tolerance, trust, and transformation—can also offer structure and insight in areas like reunification therapy, family systems work, and court-ordered treatment plans.2

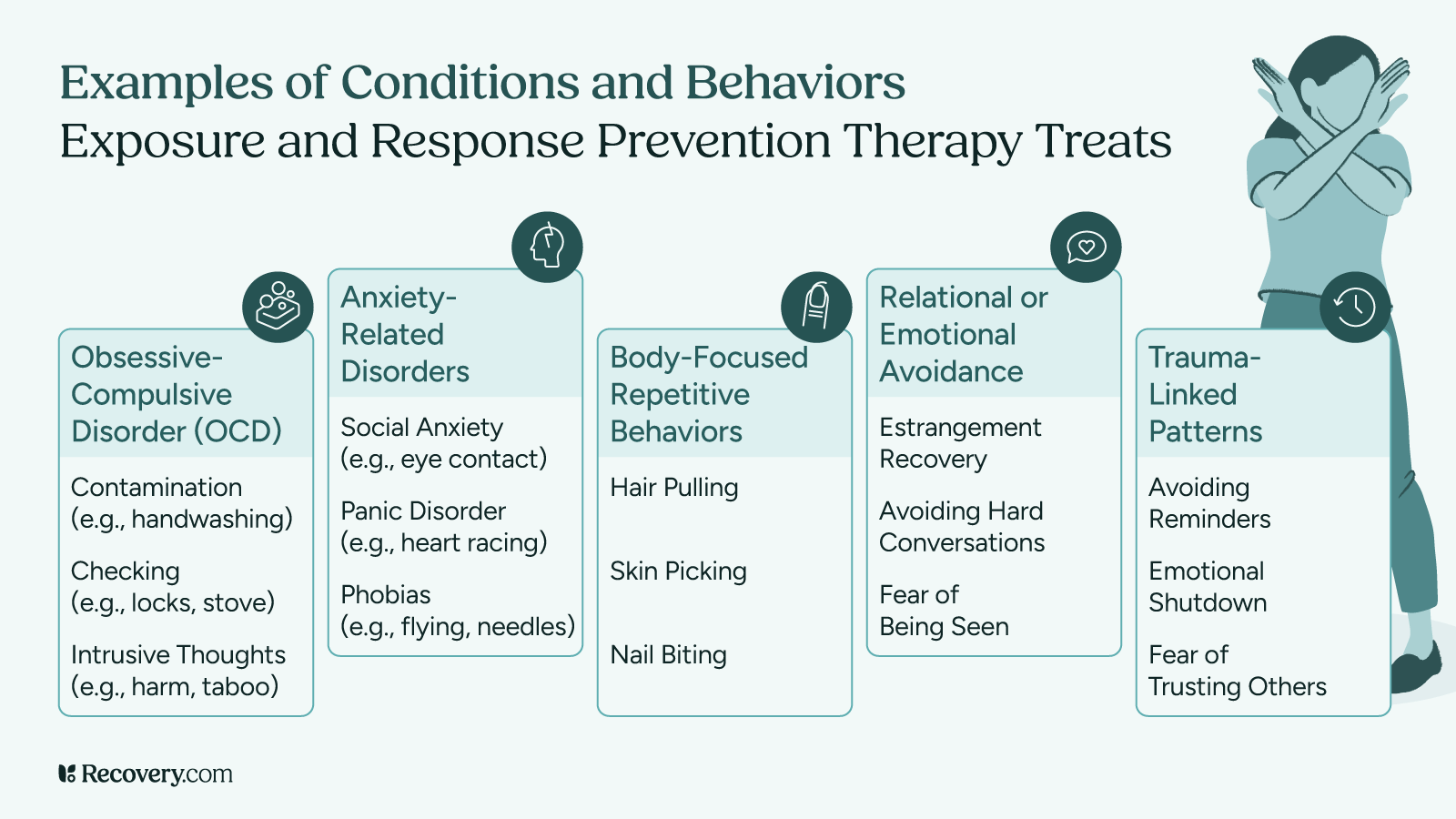

ERP is most commonly known for treating OCD symptoms, specifically obsessions, intrusive thoughts, and compulsive behaviors. But it’s not just a type of therapy reserved for those battling contamination fears or checking rituals. Its roots in cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and its reliance on gradual, anxiety-provoking exposures make it surprisingly adaptable to relational spaces—especially when those spaces are defined by avoidance, fear, or rupture.3

What ERP Really Teaches Us

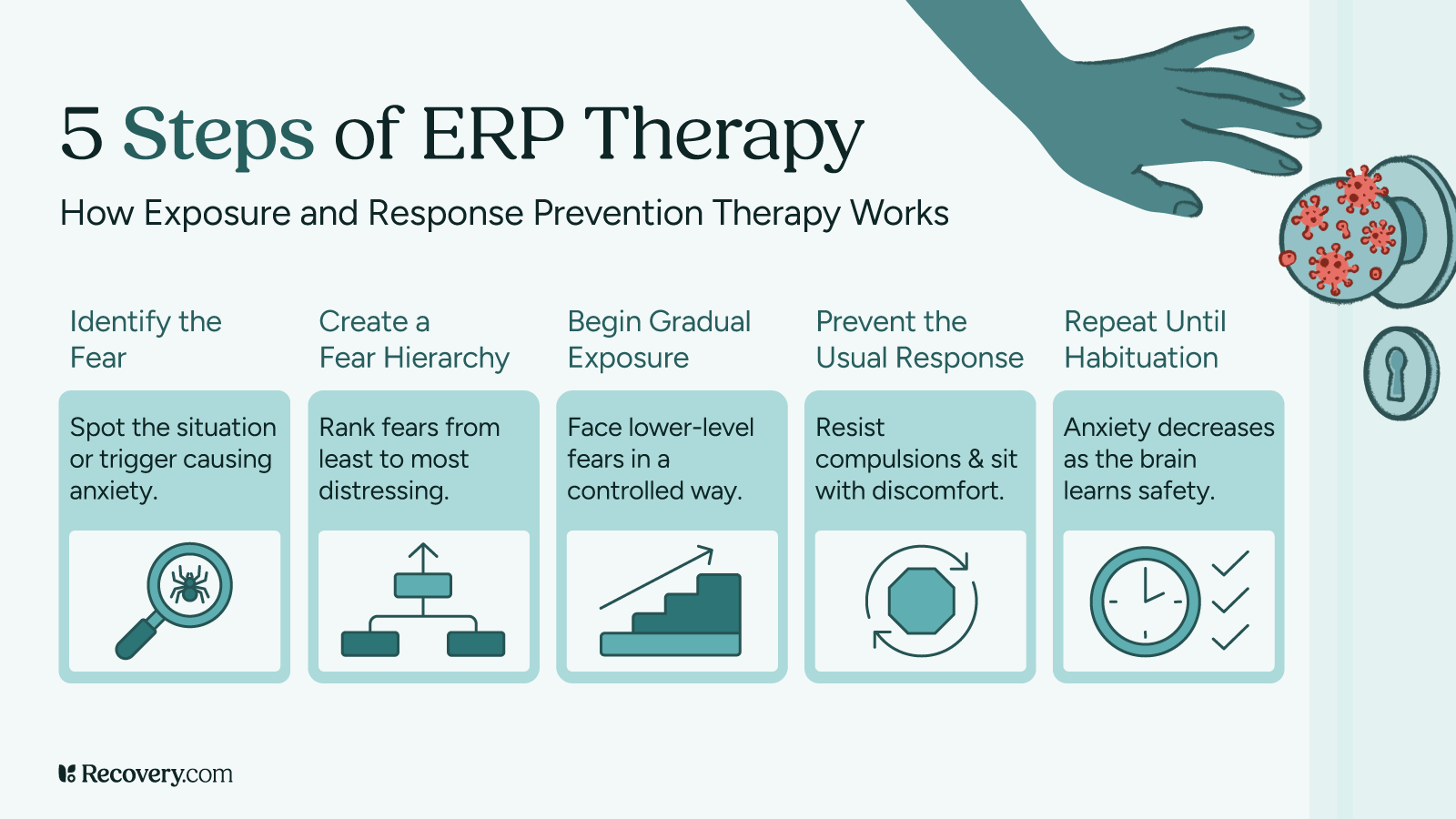

Exposure and response prevention therapy is about facing fear—and doing it differently. It invites the client to approach a feared situation or stimulus (real or imagined), while resisting the urge to engage in the habitual safety behaviors that once offered relief. That might look like resisting a hand-washing compulsion, or sitting with the discomfort of not seeking reassurance.

ERP isn’t just for obsessive thoughts—it’s for any place where fear keeps us from connection. In reunification therapy, it becomes a path back to trust, one tolerable step at a time.

The process is structured, intentional, and often uncomfortable. But in that discomfort is possibility: a new way of relating to fear. And over time, with practice, the nervous system learns something crucial—this feeling won’t last forever. I can survive it. This is the mechanism of habituation, and it’s a cornerstone of ERP’s effectiveness.

In the world of OCD treatment, this model has revolutionized care. From in vivo exposures to imaginal exposure, ERP has helped countless individuals reclaim their lives from obsessive thoughts, perfectionism, and debilitating rituals.

But what if we considered ERP’s logic not only in treating OCD, but in addressing the relational phobias that often show up in families experiencing estrangement or high-conflict divorce?

The Therapist’s Role: Skilled Guide, Not Enforcer

In this context, the mental health professional becomes a kind of behavioral cartographer—charting the terrain of fear and walking alongside families as they navigate it. Just as ERP therapists track rituals and avoidance patterns in OCD, reunification therapists can identify emotional compulsions: the urge to withdraw, to vilify, to control.

The clinician’s job is not to insist on connection, but to foster capacity—to help the child sit with what’s hard, to help the parent resist reactive behaviors, and to guide both toward emotional flexibility. These are evidence-based treatment strategies, grounded in CBT, but translated to a relational domain.4

This is particularly powerful when considered as a tool for court-ordered therapy, such as in cases involving CPS, family law, or mandated co-parenting plans. ERP’s deliberate pacing, collaborative structure, and emphasis on inhibitory learning (rewriting what the brain has learned about safety) align well with the delicate pacing required for long-term family reunification.

What ERP Is Not: A Word of Caution

While ERP therapy is an effective treatment for many anxiety-related disorders, including social anxiety, panic disorder, and OCD, it must be used with deep ethical care when applied in family contexts.5 This is not about forcing reconciliation. It is not about exposure for exposure’s sake. In families where child abuse, domestic abuse, or ongoing mental health conditions have created genuine safety concerns, no exposure should be initiated without comprehensive evaluations, trauma-informed oversight, and clear legal and clinical safeguards.

ERP is a tool—not a shortcut. And in complex family systems, it must be paired with humility, cultural sensitivity, and attunement to each individual’s readiness and consent.

Real-Life Implications: Beyond OCD, Toward Connection

The gifts of ERP reach far beyond the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Its structure teaches distress tolerance, insight into cognitive distortions, and the courage to face relational fears. These skills are invaluable in reunification therapy, co-parenting relationships, and even outpatient psychotherapy with adolescents who are navigating estrangement, identity confusion, or loyalty binds between caregivers.

For clinicians, ERP reminds us that healing doesn’t always look like comfort—it looks like commitment. A commitment to therapy, to presence, to uncertainty. And for families, it offers something far more sustainable than a quick fix: the possibility of true, hard-earned repair.6

Whether we are helping someone resist a compulsion, sit with shame, or face a loved one they haven’t spoken to in years, the heart of the work is the same: exposure to fear, and the slow, steady unlearning of resistance.

ERP as a Bridge Between Clinical Rigor and Human Repair

At its best, exposure and response prevention is about more than treating OCD symptoms. It is a way of saying: we can face what scares us, and still move toward love. That principle doesn’t just belong in psychiatry textbooks or first-line treatment guidelines—it belongs in family rooms, courtrooms, and therapy spaces where pain and possibility sit side by side.

ERP works because it reflects how healing actually happens—not in perfect conditions, but in real life, with real people, doing the brave work of showing up again and again.

In this light, we don’t just see ERP as an effective treatment for anxiety—we see it as a roadmap for restoration. Not just of functioning, but of family, belonging, and hope.

FAQs

-

1. Law, C., & Boisseau, C. L. (2019). Exposure and Response Prevention in the Treatment of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Current Perspectives. Psychology research and behavior management, 12, 1167–1174. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S211117

-

2. Reuman, L., Thompson-Hollands, J., & Abramowitz, J. S. (2021). Better Together: A Review and Recommendations to Optimize Research on Family Involvement in CBT for Anxiety and Related Disorders. Behavior therapy, 52(3), 594–606. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2020.07.008

-

3. Law, C., & Boisseau, C. L. (2019). Exposure and Response Prevention in the Treatment of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Current Perspectives. Psychology research and behavior management, 12, 1167–1174. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S211117

-

4. International OCD Foundation. (n.d.). Exposure and Response Prevention (ERP). https://iocdf.org/about-ocd/treatment/erp/

-

5. Craske, M. G., Treanor, M., Conway, C. C., Zbozinek, T., & Vervliet, B. (2014). Maximizing exposure therapy: an inhibitory learning approach. Behaviour research and therapy, 58, 10–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2014.04.006

-

6. Herren, J., Freeman, J., & Garcia, A. (2016). Using Family-Based Exposure With Response Prevention to Treat Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder in Young Children: A Case Study. Journal of clinical psychology, 72(11), 1152–1161. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22395

Our Promise

How Is Recovery.com Different?

We believe everyone deserves access to accurate, unbiased information about mental health and recovery. That’s why we have a comprehensive set of treatment providers and don't charge for inclusion. Any center that meets our criteria can list for free. We do not and have never accepted fees for referring someone to a particular center. Providers who advertise with us must be verified by our Research Team and we clearly mark their status as advertisers.

Our goal is to help you choose the best path for your recovery. That begins with information you can trust.