What Is Play Therapy? 3 Ways It Supports Kids’ Emotional Growth

Hannah is a holistic wellness writer who explores post-traumatic growth and the mind-body connection through her work for various health and wellness platforms. She is also a licensed massage therapist who has contributed meditations, essays, and blog posts to apps and websites focused on mental health and fitness.

Dr. Mala, is the Chief Clinical Officer at Recovery.com, where she develops impartial and informative resources for people seeking addiction and mental health treatment.

Hannah is a holistic wellness writer who explores post-traumatic growth and the mind-body connection through her work for various health and wellness platforms. She is also a licensed massage therapist who has contributed meditations, essays, and blog posts to apps and websites focused on mental health and fitness.

Dr. Mala, is the Chief Clinical Officer at Recovery.com, where she develops impartial and informative resources for people seeking addiction and mental health treatment.

Table of Contents

Play therapy is a type of mental health care that helps children process difficult emotions and learn skills for healthy socializing and communication. It’s based on the idea that while children don’t yet have the language to talk about complex feelings, play comes more naturally to them—and may feel like a safer way for them to express.

Play therapy is evidence-based, meaning research supports its effectiveness in helping children of all ages heal from trauma and work through behavioral challenges. It can be very worth exploring for parents or caregivers who are looking for options to support their little ones through a difficult time.

Let’s look at how this engaging, creative therapy works and the benefits it could have for your little ones.

The Basics of Play Therapy: A Child-Centered Approach

Child-centered play therapy is a therapeutic approach that’s designed to help children ages 3–12 work through emotional and behavioral challenges using toys, games, and creative activities. It’s designed to meet children where they are and allow them to communicate what’s going on internally in a way that feels more comfortable and accessible to them.

Play therapy expert and founder of the founder and director of the Center for Play Therapy Garry L. Landreth, Ed.D., LPC, RPT-S explains why kids can’t just do adult-style psychotherapy: 1

Children must be approached and understood from a developmental perspective. They are not miniature adults. Their world is one of concrete realities, and their experiences often are communicated through play. In seeking to facilitate children’s expression and exploration of their emotional world, therapists must turn loose of their world of reality and verbal expression and move into the conceptual-expressive world of children. Unlike adults, whose natural medium of communication is verbalization, the natural medium of communication for children is play and activity.

Play therapy sessions are safe, supportive settings for children to explore their feelings without judgment. It’s based on a relationship in which a registered play therapist uses special techniques to understand what children are saying through their play. This approach respects that children process experiences differently than adults and don’t have the vocabulary to describe complex feelings.

Tools Used in Play Therapy

Therapists choose the toys and materials used in play therapy carefully to encourage expression and exploration. These might include:

- Dolls and action figures for storytelling

- Art supplies for creative expression

- Legos or sand trays for building scenes

- Games that promote social skills

Each item serves a therapeutic purpose, with the goal being to help children work through specific issues or develop certain skills.

A Research-Backed Experiential Treatment

This therapy is proven effective for treating a range of childhood mental health conditions. Studies show that play therapy helps children develop better emotional regulation,2 social skills, and coping strategies. It works because it honors children’s developmental needs, all in the context of professional guidance to support their healing and growth.

How Play Therapy is Different From Regular Play

Play therapy differs from regular play in a few ways. While all play can be beneficial for children’s development,3 therapeutic play is more intentional. It’s led by specialized practitioners who structure sessions to meet specific goals and use in-depth knowledge to facilitate the process. Because they’re educated in child development and mental health, they’re trained to recognize what children are trying to express and identify themes that emerge from these sessions.

A good play therapist should plan sessions so they steer your child toward progress over time.

Play Therapy’s 3 Main Goals

Play therapy serves 3 key functions that support your child’s mental health and emotional development:

1. Communication

This is the foundation of the effectiveness of play therapy. Most young children lack the vocabulary or emotional maturity to articulate complex emotions like grief, anger, or confusion—especially if they have conflicting feelings.4 A lot of little ones find it easier and more natural to express these emotions through play. They might use puppets to act out a conflict they witnessed at home, for example, or use sand play to build structures that represent their inner emotional landscape. This kind of communication bypasses the limitations of verbal expression and gives mental health practitioners a window into what children are really experiencing.

2. Emotional Processing

Children often carry difficult experiences in their bodies and minds without fully understanding (or integrating) what happened to them. Play is a safe container for working through traumatic experiences5 at their own pace. For example, a child who experienced medical trauma might repeatedly give shots to stuffed animals, allowing them to eventually gain mastery over a scary experience. This kind of play helps children process emotions, reduce anxiety, and develop a sense of control over their experience.

3. Skill Building

This aspect of play therapy focuses on developing healthy coping strategies and social abilities. Through guided play experiences, children learn emotional regulation techniques, problem-solving skills, and healthy ways of relating to others. They might practice conflict resolution through role-playing games,6 develop patience through structured activities, or build self-confidence by mastering new challenges in a supportive environment.

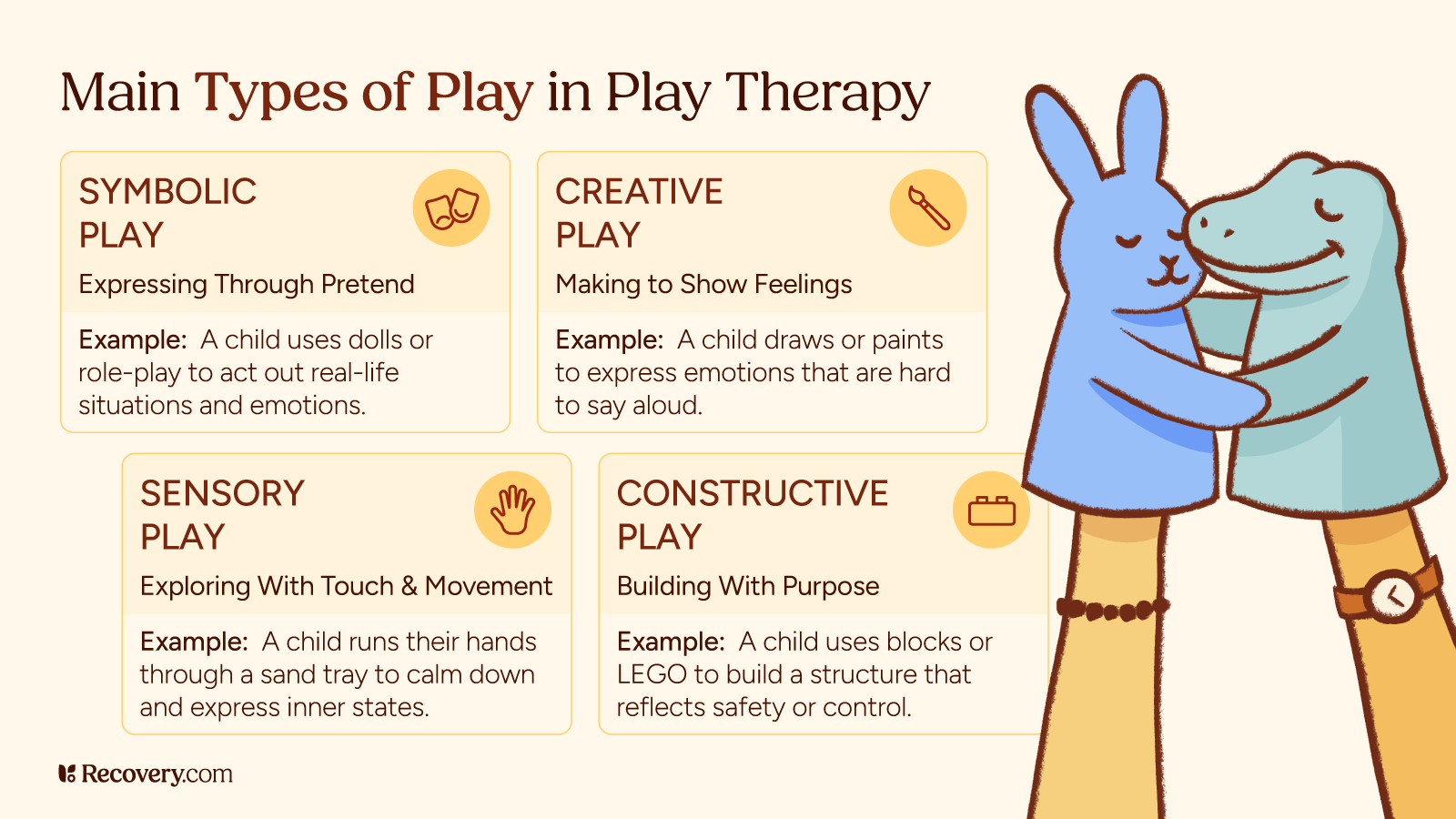

Types of Play Therapy

Play therapy encompasses 2 primary approaches that therapists use depending on the child’s needs, personality, and therapeutic goals:

Directive Play Therapy

In directive (or focused) play therapy,7 the therapist actively guides the session. They choose specific toys, games, or exercises designed to address particular issues or teach certain skills. For example, a they might use a specific art activity to help a child express feelings about their parents’ divorce, or use a game designed to build social skills for someone who struggles with peer relationships.

This form of therapy works well for children who benefit from clear structure, have specific behavioral goals, or need direct skill instruction.

Non-Directive Play Therapy

The non-directive approach8 follows the child’s natural lead, allowing them to choose activities and direct the session’s flow. The therapist holds a safe space, but lets the child decide how to use different play materials. This approach is based on trust that children naturally gravitate toward what they need to heal and process.

A lot of experienced play therapists blend elements from both approaches based on what each child needs.

What Age Groups Benefit From Play Therapy?

Play therapy is most commonly used for children between the ages of 3 and 12, though the approach can be adapted for younger and older kids depending on their needs. This age range is the time when children naturally tend to explore the world, process experiences, and express emotions through the use of play.

Preschool Children (Ages 3–5)

Play therapy works well for this age group because they have limited verbal skills but rich imaginations. At this stage, children process experiences through symbolic representation9 and repetitive play. A 4-year-old might not be able to explain feeling scared about starting school, but they can show these feelings by having toy animals hide or by repeatedly building and knocking down structures.

School-Age Children (Ages 6–12)

Children in this age can still benefit from play therapy, though sessions might involve more verbal processing alongside play activities. These children can engage in more complex games, understand rules better, and begin to make connections between play and real life.10 They might like board games that teach problem-solving skills or art projects that help them express complicated family situations.

Teens and Adolescents

While play therapy is less commonly used with teenagers, some adolescents respond well to modified approaches that incorporate creative activities like music, art, or drama.11 The main factors are the individual child’s developmental level, interests, and comfort with play-based expression—not just chronological age.

Issues Play Therapy Can Address

Play therapy is effective for treating a wide range of conditions12 in children. The most common include:

- Trauma and PTSD from abuse, domestic violence, accidents, or medical procedures

- Anxiety and depression that cause withdrawal, sleep problems, or persistent worry

- Behavioral problems including aggression, defiance, and difficulty following rules

- Family transitions like divorce, the death of a loved one, or major moves

- Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), autism spectrum disorders that benefit from flexible, sensory-rich approaches

- Learning disabilities that affect academic performance and self-esteem

- Difficulties with social skills and problems with peer relationships

- Grief and loss following deaths or significant life changes

This more relaxed approach to therapy creates a safe space where children can process difficult experiences at their own pace.

The Benefits of Play Therapy for Children

1. It Develops Emotion Regulation

Children who participate in play therapy often experience improvements in their well-being that extend far beyond the therapy room. Many develop stronger emotional regulation skills13 like learning to recognize when they feel overwhelmed and using healthy ways to calm themselves down.

2. It Addresses Social Anxiety and Improves Communication Skills

Play therapy can also decrease social anxiety14 and improve communication skills. Better communication strengthens parent-child relationships and helps kids advocate for themselves in school and social situations.

3. It Builds Confidence and Self-Worth

Most importantly, play therapy helps children rebuild their confidence15 and self-worth. As they work through challenges in a supportive environment, many discover inner strengths they didn’t know they had. This growing self-assurance often translates into improved academic performance, stronger friendships, and more willingness to try new things.

Because play therapy is designed to be child-centered and flexible, your therapist can adapt it to meet your child’s needs.

What to Expect in Play Therapy Sessions

Play therapy sessions usually last 45–50 minutes and occur weekly, though frequency may vary based on your family’s schedule. The therapist will create a consistent, safe environment filled with carefully selected toys and materials designed to encourage expression and exploration.

Parent involvement varies depending on the child’s age and treatment goals. Some therapists include parents in some sessions, while others work individually with children and meet with parents separately to discuss progress and strategies for home. It all depends on your therapist’s approach and your child’s needs.

Progress in play therapy often happens gradually,16 depending on your child’s natural pace. Your therapist should communicate regularly about your child’s development and adjust treatment approaches as needed.

How to Find a Play Therapist

When searching for a play therapist, look for licensed mental health professionals who have specialized play therapy training. This includes licensed therapists, social workers, and school counselors who have completed additional play therapy certification. Many therapists hold credentials from organizations like the Association for Play Therapy, which requires specific education and supervised experience in this field.

Ask potential therapists about their experience working with children who have similar challenges to your child’s situation. Learn about their therapeutic approach, session structure, and how they involve parents in the treatment process. Most qualified play therapists will offer an initial consultation to discuss your child’s needs and determine if play therapy is an appropriate fit.

Insurance coverage for play therapy varies, so contact your insurance provider to understand your benefits. Many therapists offer sliding scale fees or payment plans to make treatment more accessible. Recovery.com can help you locate qualified play therapists in your area who meet your needs and preferences.

FAQs

Q: How long does play therapy take to work?

A: The total length of the treatment episode varies based on your child’s progress, but most children start to show some improvement within 6–8 sessions. Some children benefit from short-term intervention; others require longer-term support.

Q: Is play therapy covered by insurance?

A: Many insurance plans cover play therapy if it’s provided by a licensed mental health professional. Check with your insurance provider for more information about your coverage. The team at your treatment center may also be able to talk to your provider and help you sort out insurance details.

Q: Can parents observe sessions?

A: Therapist policies on parent observation vary. Some allow occasional observation, while others believe children express themselves more freely without parents present. Discuss this preference with your chosen therapist.

Q: What if my child doesn’t want to play?

A: Skilled play therapists can work with reluctant children by starting with less threatening activities and gradually building comfort. Children should never be forced to participate in activities that make them uncomfortable.

-

Landreth, Garry L. Play Therapy: The Art of the Relationship. Routledge, 2012.

-

Chinekesh A, Kamalian M, Eltemasi M, Chinekesh S, Alavi M. The effect of group play therapy on social-emotional skills in pre-school children. Glob J Health Sci. 2013 Dec 24;6(2):163-7. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v6n2p163. PMID: 24576376; PMCID: PMC4825459.

-

Barnett, L. A. (1990). Developmental Benefits of Play for Children. Journal of Leisure Research, 22(2), 138–153. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222216.1990.11969821

-

Harter, S. (1977). A cognitive-developmental approach to children's expression of conflicting feelings and a technique to facilitate such expression in play therapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 45(3), 417–432. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.45.3.417

-

Parker, M. M., Hergenrather, K., Smelser, Q., & Kelly, C. T. (2021). Exploring child-centered play therapy and trauma: A systematic review of literature. International Journal of Play Therapy, 30(1), 2–13. https://doi.org/10.1037/pla0000136

-

Rosselet, J. G., & Stauffer, S. D. (2013). Using group role-playing games with gifted children and adolescents: A psychosocial intervention model. International Journal of Play Therapy, 22(4), 173–192. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034557

-

RPT-S, Elsa Soto Leggett, PhD, LPC-S., and Jennifer N. Boswell RPT PhD, LPC-S, NCC. Directive Play Therapy: Theories and Techniques. Springer Publishing Company, 2016.

-

Wilson, Kate, and Virginia Ryan. Play Therapy: A Non-Directive Approach for Children and Adolescents. Elsevier Health Sciences, 2006.

-

Veraksa, A., & Veraksa, N. (2015). Symbolic representation in early years learning: The acquisition of complex notions. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 24(5), 668–683. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2015.1035539

-

Koukourikos K, Tsaloglidou A, Tzeha L, Iliadis C, Frantzana A, Katsimbeli A, Kourkouta L. An Overview of Play Therapy. Mater Sociomed. 2021 Dec;33(4):293-297. doi: 10.5455/msm.2021.33.293-297. PMID: 35210953; PMCID: PMC8812369.

-

Berghs M, Prick AJC, Vissers C, van Hooren S. Drama Therapy for Children and Adolescents with Psychosocial Problems: A Systemic Review on Effects, Means, Therapeutic Attitude, and Supposed Mechanisms of Change. Children (Basel). 2022 Sep 6;9(9):1358. doi: 10.3390/children9091358. PMID: 36138667; PMCID: PMC9497558.

-

Chase, Selena. “The Effectiveness of Play Therapy for Children with Behavioral and Emotional Problems: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials.” Journal of Public Health & Environment, vol. 5, no. 2, Nov. 2022, pp. 1–10. www.journal-phe.online, https://www.journal-phe.online/5/2/164.

-

Hoffman, L., Prout, T. A., Rice, T., & Bernstein, M. (2023). Addressing Emotion Regulation with Children: Play, Verbalization of Feelings, and Reappraisal. Journal of Infant, Child, and Adolescent Psychotherapy, 22(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/15289168.2023.2165874

-

Indian Journal of Forensic Medicine & Toxicology Year : 2018, Volume : 12, Issue : 1 First page : ( 198) Last page : ( 203) Print ISSN : 0973-9122. Online ISSN : 0973-9130. Article DOI : 10.5958/0973-9130.2018.00039.7

-

Guindon, Mary H. Self-Esteem Across the Lifespan: Issues and Interventions. Taylor & Francis, 2009.

-

Kottman, Terry, and Jeffrey S. Ashby. Play Therapy: Basics and Beyond. John Wiley & Sons, 2024.

Our Promise

How Is Recovery.com Different?

We believe everyone deserves access to accurate, unbiased information about mental health and recovery. That’s why we have a comprehensive set of treatment providers and don't charge for inclusion. Any center that meets our criteria can list for free. We do not and have never accepted fees for referring someone to a particular center. Providers who advertise with us must be verified by our Research Team and we clearly mark their status as advertisers.

Our goal is to help you choose the best path for your recovery. That begins with information you can trust.