Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT): An Evidence-Based Path to Recovery

As a Clinical Research Specialist, writer, and person with lived experience in mental health recovery, Grace blends clinical research with honest storytelling to inspire healing and hope. In her free time, she enjoys writing books for young adults, an age when she needed stories the most.

Dr. Mala, is the Chief Clinical Officer at Recovery.com, where she develops impartial and informative resources for people seeking addiction and mental health treatment.

As a Clinical Research Specialist, writer, and person with lived experience in mental health recovery, Grace blends clinical research with honest storytelling to inspire healing and hope. In her free time, she enjoys writing books for young adults, an age when she needed stories the most.

Dr. Mala, is the Chief Clinical Officer at Recovery.com, where she develops impartial and informative resources for people seeking addiction and mental health treatment.

Table of Contents

- What Is Medication Assisted Treatment?

- Medication Assisted Treatment For Alcohol

- Naltrexone | Vivitrol and ReVia

- Disulfiram | Antabuse

- Acamprosate | Campral

- Medication Assisted Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder

- Methadone | Dolophine and Methadose

- Buprenorphine | Suboxone, Sublocade, Subutex, Zubsolv, and Bunavail

- Naltrexone | Vivitrol and ReVia

- MAT to Quit Smoking | Nicoderm CQ, Nicorette, Nicotrol

- Bupropion and Varenicline | Zyban, Chantix

- New and Emerging Medication Assisted Treatments

- Top 5 Myths About MAT

What Is Medication Assisted Treatment?

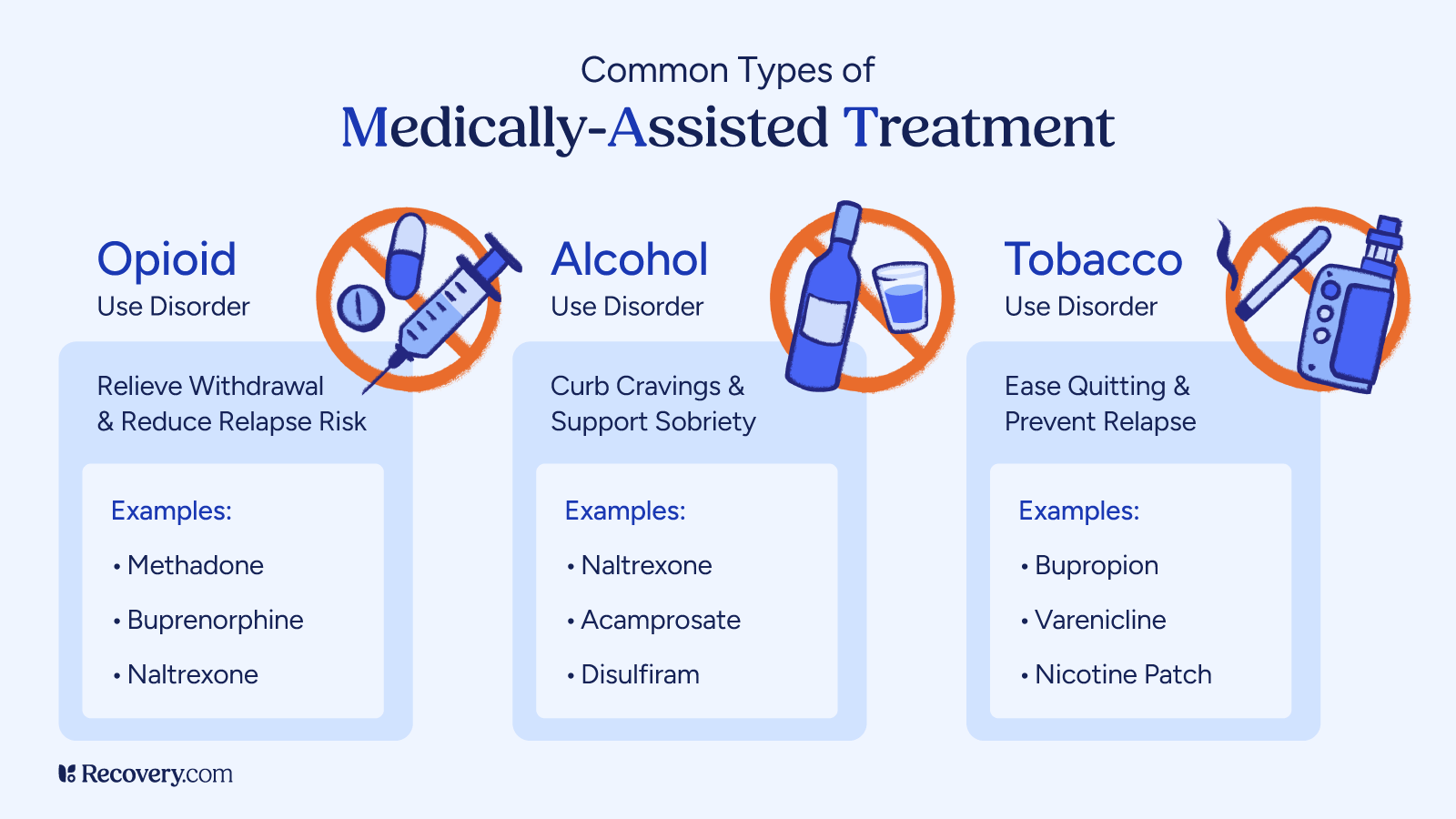

Medication-assisted treatment (MAT) is a proven approach for treating substance use disorders, including opioid use disorder (OUD) and alcohol use disorder (AUD).

It combines FDA-approved medications such as methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone with counseling and behavioral therapies to address both the physical and psychological aspects of addiction.

Unlike treatment models that rely solely on abstinence, MAT targets the brain changes caused by substance use, helping to stabilize brain chemistry, reduce withdrawal symptoms, and control cravings. This allows patients to engage more fully in therapy and other recovery-focused activities.

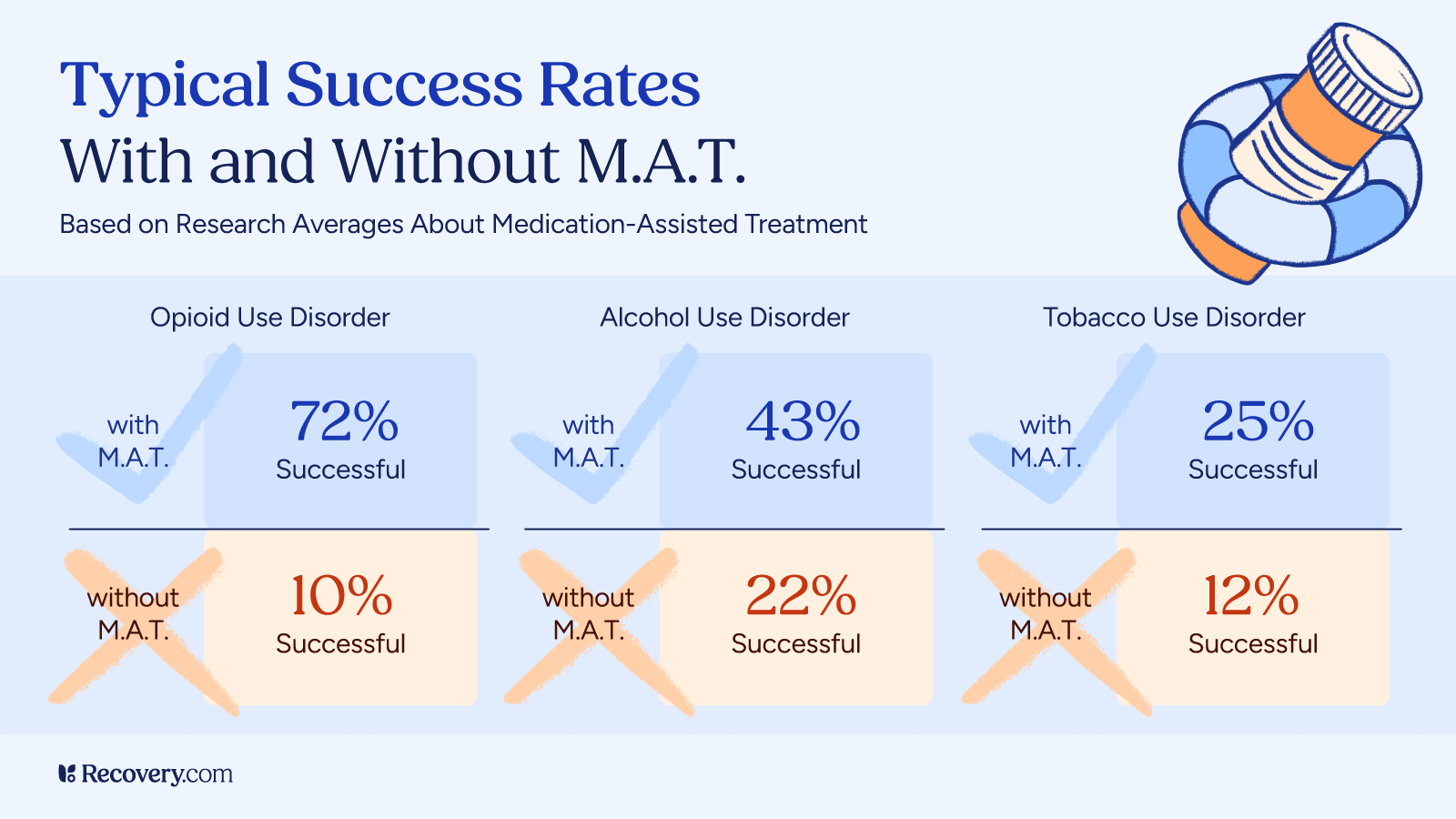

MAT is recognized as one of the most effective interventions for improving treatment retention, reducing illicit drug use, and lowering the risk of opioid overdose.

The History of Medication Assisted Treatment

The history of MAT can be traced back to the 1960s when methadone was first utilized as a treatment for heroin addiction and public health approach to drug addiction.1 Its introduction marked a significant shift in how addiction and substance abuse treatment was perceived and treated.

Before this, traditional treatment methods focused primarily on counseling and abstinence, often leaving many patients struggling with withdrawal symptoms and cravings without adequate support.

Research has since demonstrated that the use of medications can help stabilize patients, reduce cravings, and lower the risk of relapse, leading to better long-term outcomes.2

What You Need to Know

One of the primary advantages of MAT is its ability to target the biological aspects of addiction. Medications such as buprenorphine and naltrexone work by modulating neurotransmitter activity in the brain, addressing the underlying physiological components of addiction.3

By alleviating withdrawal symptoms and reducing the euphoric effects of substances, MAT allows people to engage more fully in counseling and other therapeutic interventions while focusing on the medical treatment of substance use disorders.

Additionally, MAT boasts evidence-based effectiveness. Studies have shown that when combined with counseling, MAT can significantly improve retention in treatment programs, reduce illicit drug use, and lower the risk of overdose. Medications used in MAT are also regulated by the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA)for safety and effectiveness.4,5

You can find other regulations and stipulations on the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS) official website.6 This dual approach not only helps patients manage their addiction but also confronts the psychological, behavioral health, and emotional challenges that accompany recovery.

Medication Assisted Treatment For Alcohol

Medication-assisted treatment (MAT) is not only effective for opioid use disorder, it can also play a key role in recovery from alcohol use disorder (AUD). By combining FDA-approved medications with counseling and behavioral therapies, MAT addresses both the physical and psychological aspects of alcohol dependence.

Medications such as naltrexone, disulfiram, and acamprosate each work in different ways to reduce cravings, block the rewarding effects of alcohol, or support brain stabilization during recovery. These treatment options can make it easier for patients to focus on therapy, avoid relapse, and maintain long-term sobriety and psychosocial wellness.

The following includes more information about specific types of MAT for AUD.

Naltrexone | Vivitrol and ReVia

What Is It?

Naltrexone is an opioid receptor antagonist that blocks the euphoric effects of alcohol and reduces cravings.7

How Does It Work?

Naltrexone blocks the effects of alcohol at the receptor level, meaning receptors in the brain can’t receive them. This prevents any euphoric effects if someone drinks alcohol, and can also reduce cravings.

How Is It Taken?

It can be given as a daily oral tablet or as a monthly extended-release injection (Vivitrol).

Benefits

Naltrexone reduces cravings for alcohol and prevents pleasurable effects, which can make people generally uninterested in alcohol. A study even found that Naltrexone can reduce relapse rates by 50%, compared to not taking it.8

Side Effects

Side effects of naltrexone include:9

- Nausea

- Headache

- Fatigue

- Dizziness

- Lost appetite

Serious but uncommon risks include liver damage, infection (if injected), depression, and allergic reactions.

Who It’s For (and Who It’s Not For)

Naltrexone is for people diagnosed with AUD who have a strong desire to quit drinking, but can get overwhelmed by cravings. Patients can begin naltrexone once they’ve passed through the acute detox phase and have no or minimal alcohol left in their bodies.

For that reason, naltrexone isn’t a good fit for someone in acute withdrawal or someone who is actively drinking. It can cause side effects and even make symptoms feel worse if alcohol isn’t mostly out of their system.

Disulfiram | Antabuse

What Is It?

Disulfiram helps people stay in recovery from alcohol use disorder by causing extremely unpleasant reactions to alcohol. This discourages any alcohol use—even tiny amounts can trigger reactions like flushing, nausea, pounding heart, and dizziness.

How Does It Work?

Disulfiram causes what’s called the disulfiram-alcohol reaction, which means a compound, acetaldehyde, has built up in the blood.10 That’s what causes the unpleasant physical reactions. These effects can last 1-3 hours.

How Is It Taken?

Disulfiram comes in a pill you take once a day. Any alcohol in your system will trigger the reactions, so it’s important to go at least 24 hours without a drink before taking disulfiram. Your prescribing doctor will explain what else may trigger it too, like mouthwashes with alcohol.

Benefits

Disulfiram deters alcohol use, which means people are much less likely to drink—even when cravings are strong. People taking disulfiram have a lower risk of relapse and generally stay in recovery longer, but motivation is a major factor in its success.11 Combining disulfiram with a behavioral therapy can help with motivation.

Side Effects

Disulfiram is designed to cause side effects, but not all are intended. These are some potential side effects, going from common to rare:

- Vomiting

- Fatigue

- Rash

- Shortness of breath

- Liver failure

- Heart failure

- Psychosis

Who It’s For (and Who It’s Not For)

Disulfiram is for people who have stopped drinking alcohol and want to maintain that. They may want extra assurance and protection against resuming alcohol use, especially if they’re newly sober.

Motivation is a major factor in disulfiram’s success. If people stop taking it, they’ll stop having negative reactions to alcohol, so they must be ready to commit. It can take upwards of two weeks for disulfiram to leave someone’s system, so one missed dose won’t erase its potency, but those who decide to permanently stop taking it risk returning to substance use.

Acamprosate | Campral

What Is It?

Acamprosate stabilizes your brain after alcohol has destabilized it.12

How Does It Work?

Acamprosate lowers levels of excitatory neurons, which can make people feel calmer and less agitated. This can lead to reduced cravings for alcohol.

How Is It Taken?

Acamprosate comes in a pill that you typically take three times a day.

Benefits

Acamprosate has been proven effective for alcohol use disorder recovery.13 It’s most beneficial when combined with therapy, as it doesn’t treat underlying causes of alcohol use disorder.

Side Effects

Common side effects for acamprosate include

- Diarrhea

- Headache

- Fatigue

- Irritability

- Muscle weakness

Kidney damage is a rare but serious side effect.

Who It’s For (and Who It’s Not For)

Acamprosate is for those nearing the end of detox or in early recovery. It essentially serves as a ‘settling’ tool that can make people less prone to wanting alcohol. It is not for those who want something that directly impacts cravings, or who want negative reactions to alcohol to further discourage their use.

Medication Assisted Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder

For people living with opioid use disorder (OUD), medication-assisted treatment (MAT) offers a proven, evidence-based path to recovery.

By combining FDA-approved medications, such as methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone, with counseling and behavioral therapies, MAT addresses both the physical dependence and the psychological aspects of opioid addiction. Referrals to social services and community support groups further enhance the treatment experience

These medications can reduce withdrawal symptoms, control cravings, and block the euphoric effects of opioids, making it easier for patients to focus on recovery. Whether provided in an opioid treatment program (OTP), primary care setting, or specialty clinic, MAT for the treatment of OUD has been shown to improve treatment retention, reduce illicit opioid use, and lower the risk of opioid overdose.

Methadone | Dolophine and Methadose

What Is It?

Methadone is a long-acting opioid agonist that helps to stave off withdrawal symptoms and cravings for people with opioid use disorder (OUD).

How Does It Work?

Methadone works by binding to the same opioid receptors in the brain as other opioids, but it does so in a way that’s minimal and controlled. This alleviates withdrawals because methadone is still bonding with receptors and filling empty spaces, but without euphoria.

How Is It Taken?

Methadone most often comes as a pill, but injections may be used when rapid detox is needed. Patients will go to a methadone MAT clinic to receive their daily dose and take it under supervision, so staff know that they’re getting the right amounts, not in crisis, and not misusing their dose. As patients remain in an MAT program, they may be allowed to take pills home with them and go to the clinic every other day, for example.

Benefits

Methadone is a major tool in preventing relapse and overdoses.14 It contributes to long-term sobriety by reducing cravings and making withdrawals less uncomfortable, which can reduce relapses.

Side Effects

Common side effects of methadone include:

- Dizziness

- Nausea

- Sweating

- Weight gain

And, though rare, serious side effects can cause circulation issues, shallow breathing, and heart complications. Since methadone functions similarly to other opioids, there’s also a possibility of developing an addiction to methadone at high doses.

Who It’s For (and Who It’s Not For)

Methadone is for those in acute detox from opioids and those wanting to maintain their sobriety by managing cravings. Methadone isn’t for people who take benzodiazepines (because both benzos and methadone are sedating) or have breathing problems. Those in active addiction aren’t a good fit for methadone either, as it may be difficult or impossible to take doses as prescribed.

Buprenorphine | Suboxone, Sublocade, Subutex, Zubsolv, and Bunavail

What Is It?

Buprenorphine is a synthetic opioid and type of MOUD that helps alleviate withdrawals and reduces cravings for opioids.3

How Does It Work?

Buprenorphine is a partial agonist and antagonist for opioid receptors in the brain, which means it dampens the effects of opioids and can even boost mood. Unlike methadone, it has a ‘ceiling’ to its effects, so it’s less likely to lead to addiction.

How Is It Taken?

Buprenorphine is available as a daily pill, a sticker-like patch that goes on your skin (think of a nicotine patch), monthly injections, or as implants that slowly release buprenorphine for months.

Benefits

Buprenorphine makes opioid withdrawals less uncomfortable and reduces overwhelming cravings, so people can focus on treatment.15 It can keep people in treatment longer, leading to improved recovery rates and much lower risks of overdose. It’s also considered to be safer than methadone because its effects have a limit.

Side Effects

Buprenorphine is generally well-tolerated, but can cause nausea, dizziness, and sleepiness. Severe but rare side effects include shallow breathing, liver damage, and potentially worsening withdrawal symptoms if it’s started too soon after opioid use.

Who It’s For (and Who It’s Not For)

Buprenorphine is for those who want to stop taking licit or illicit opioids and do not need daily or regular check-ins to maintain their sobriety (as you would getting methadone). It may not be the right fit for people newly in recovery, who would benefit from more constant support, or people with respiratory or liver issues.

Naltrexone | Vivitrol and ReVia

What Is It?

Naltrexone is an opioid receptor antagonist that blocks the effects of opioids and reduces cravings for both opioid use disorder (OUD) and alcohol use disorder (AUD). It’s not to be confused with naloxone, a similar-sounding but different medication that reverses opioid overdoses.

How Does It Work?

Naltrexone binds to opioid receptors in the brain without activating them, preventing any other opiate from producing euphoric effects.

How Is It Taken?

Naltrexone is available as a daily oral tablet (ReVia) or as a monthly extended-release injectable (Vivitrol) administered by a healthcare provider. Before starting naltrexone, patients must complete detox and be free of opioids to avoid triggering withdrawal symptoms.

Benefits

Naltrexone helps prevent relapse by blocking euphoric effects and reducing cravings. In people with OUD, it can protect against overdose if opioids are used, although the risk still exists if high doses are taken. Its non-addictive nature makes it a valuable long-term option for many patients.

Side Effects

Common side effects include nausea, headache, dizziness, fatigue, and decreased appetite. Rare but serious risks include liver damage, depression, and injection site reactions for the injectable form.

Who It’s For (and Who It’s Not For)

Naltrexone is for patients motivated to maintain sobriety from opioids who have already completed detox and have no opioids in their system. It is not suitable for those currently using opioids, in acute withdrawal, with significant liver disease, or who may have difficulty adhering to follow-up care.

MAT to Quit Smoking | Nicoderm CQ, Nicorette, Nicotrol

What Is It?

These over-the-counter or prescription medications, called nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), deliver nicotine without the harmful chemicals in tobacco smoke. They help people quit smoking or reduce smoking by easing withdrawal symptoms and cravings.

How Does It Work?

These medications provide a steady, controlled dose of nicotine to reduce cravings and withdrawal discomfort, helping people lower their nicotine intake. Instead of the quick, intense nicotine hit from cigarettes or vapes, NRT gives your brain smaller, slower doses—allowing you to taper down gradually.

How Is It Taken?

NRT comes as patches you wear on your skin, as gum, nasal sprays, and as lozenges. It can also come in an inhaler. You can use them every day for as long as you need; NRTs are sold in tapering doses so you can take less and less over time. Depending on someone’s usual use of nicotine, they may need to taper down across weeks or even months.

Benefits

NRTs have been found to increase quit rates by 50–70%, reduce cravings, and help people lower their nicotine consumption over time, which typically has better outcomes than stopping cold-turkey.16

Side Effects

Common side effects of NRTs include

- Skin irritation (when using a patch)

- Mouth soreness (from lozenges or gum)

- Hiccups

- Nose discomfort

Rare but severe side effects include an irregular heartbeat or allergic reactions.

Who It’s For (and Who It’s Not For)

NRTs are for adults who want to stop smoking, but haven’t had success when stopping all at once or don’t want to experience withdrawals. It’s not a good fit for people who want to cut nicotine out of their life completely—at least not right away. Children and those pregnant or breastfeeding aren’t a good fit for NRT either.

Bupropion and Varenicline | Zyban, Chantix

What Is It?

Buproprion is a prescription antidepressant that also helps reduce nicotine cravings.

How Does It Work?

Buproprion increases the neurotransmitters dopamine and norepinephrine to reduce cravings and withdrawal symptoms. It calms the brain’s nicotine “alarm” and boosts mood, making cravings feel less intense.

How Is It Taken?

Buproprion is taken as a pill, usually twice a day, starting 2 weeks before someone intends to quit smoking.

Benefits

Buproprion has been found to double quit rates, and even helps with mood and weight.17 It works well combined with NRT, but can be used on its own.

Side Effects

Buproprion’s common side effects include

- Dry mouth

- Insomnia

- Headache

Severe, but much less common side effects include seizures and allergic reactions.

Who It’s For (and Who It’s Not For)

Buproprion is for adults who’re motivated to quit smoking and may not have had success trying on their own. It requires a prescription from a medical doctor or psychiatrist. Someone who does not want to take medications may not be the right fit for buproprion, along with people with seizures, eating disorders, or withdrawal symptoms from drugs or alcohol.

New and Emerging Medication Assisted Treatments

GLP-1 Agonists (e.g., Semaglutide – Ozempic / Wegovy)

- What’s happening: Originally designed for diabetes and weight loss.

- Emerging use:Studies show semaglutide can reduce alcohol consumption and cravings by about 40% and even lower overdose rates in opioid use disorder by 40%.18

- Anecdote: Onereport found a man experienced majorly reduced cravings for cocaine, which he’d been taking for years, when he started semaglutide for weight loss.19

Psychedelic-Assisted Therapies (e.g., Ibogaine, Psilocybin, MDMA)

- Ibogaine:

- Ibogaine is a psychoactive substance that’s illegal in America, but currently undergoing trials to be FDA-approved for addiction treatment. It acts on multiple neurotransmitter systems to reduce withdrawal symptoms and cravings.

- Some have experienced serious side effects, like heart attacks, so researchers and clinicians are proceeding cautiously.

- MDMA-Assisted Psychotherapy:

- While initially studied for PTSD, researchers are evaluating its use in alcohol use disorder, other substance use disorders, and in improving therapy due to its ability to open the mind.

- MDMA-assisted therapy has receivedFDA Breakthrough Therapy designation for PTSD, with new drug applications expected soon.20

- Psilocybin and Other Psychedelics:

- These are generally considered safer than ibogaine, and potentially closer to FDA approval for use in America.

Lofexidine (Lucemyra)

- Used for opioid withdrawal symptoms, lofexidine was approved in 2018 as the first non-opioid FDA-approved treatment.21

- It calms the body’s “fight or flight” response during withdrawal, but doesn’t stop symptoms entirely.

Nalmefene (for Alcohol Dependence)

- Approved in the EU (marketed as Selincro), nalmefene is used as needed to reduce heavy drinking.22 It blocks opioid receptors, making alcohol use less pleasurable.

- It’s taken only on days when someone expects to drink, theoretically helping them have less.

Vaccines Against Addictive Substances

- Vaccines like this are still in the investigational phase, but their potential is exciting.

- These “addiction vaccines” encourage the body’s immune system to neutralize drugs before they reach the brain and produce addictive effects, like euphoria.

With individualized treatment plans and support from qualified providers, MAT offers a compassionate, evidence-based pathway toward lasting recovery. From methadone and buprenorphine to naltrexone, medication-assisted treatment (MAT) offers life-saving options for people living with opioid use disorder and other substance use disorders.

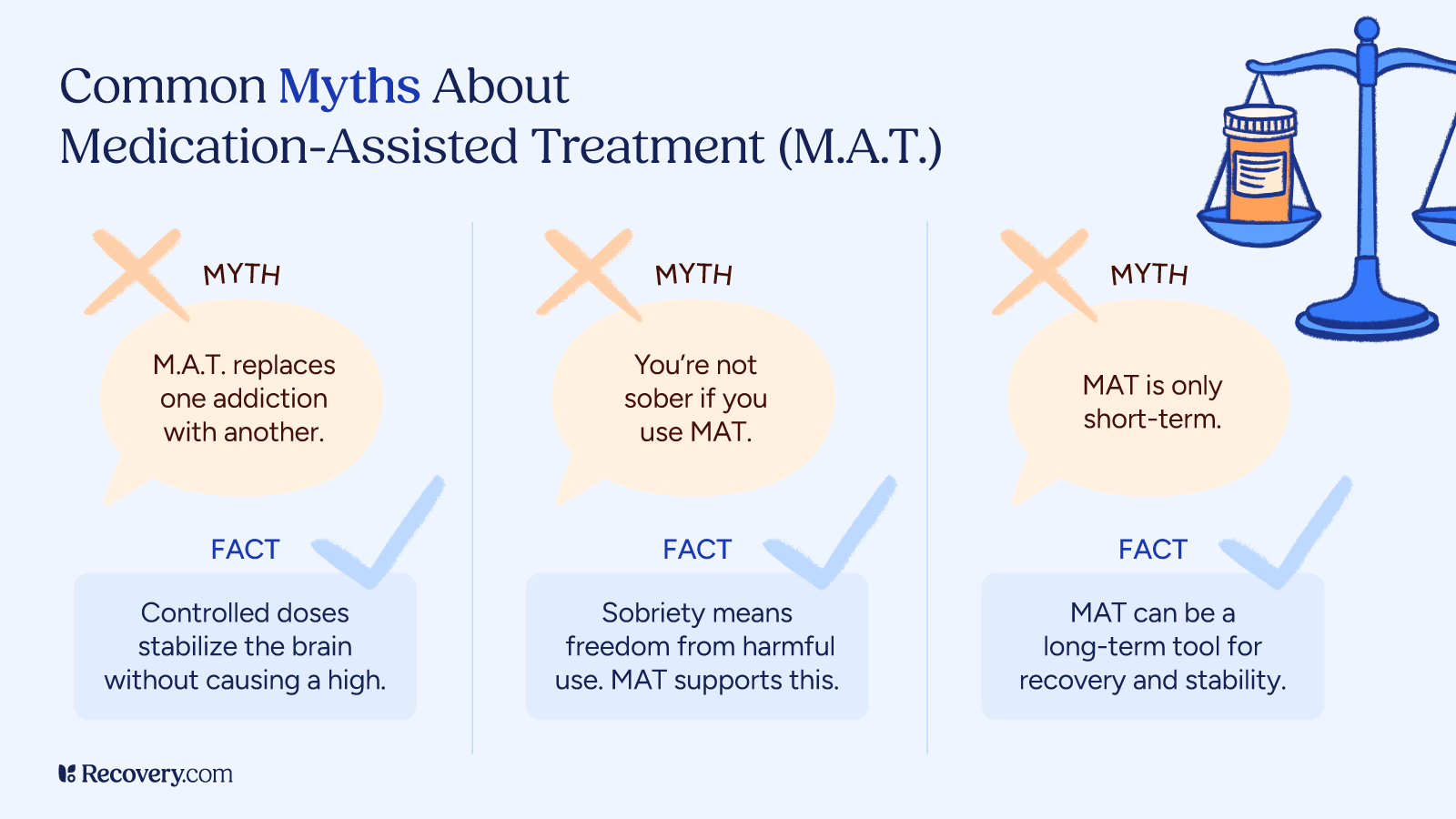

Top 5 Myths About MAT

- “MAT is just replacing one addiction with another.”

- This myth is pervasive, but untrue. Medications used in MAT (like methadone, buprenorphine, naltrexone) are prescribed in controlled doses under medical supervision. They do not produce a high when used correctly—they stabilize brain chemistry, reduce cravings, and enable recovery rather than perpetuate addiction.

- “People on MAT aren’t truly sober or in real recovery.”

- Sobriety means more than abstinence. It means regaining stability, health, and control. Major health organizations, like the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), endorse MAT as a valid, evidence-based path to recovery.

- “MAT should only be short‑term.”

- Recovery plans vary. Some people will need MAT for months, or even years. Some may only require it during acute detox. The longer someone does MAT, the lower their risk of relapse becomes.22

- “MAT is only for severe or long‑term addiction cases.”

- MAT isn’t just a last‑resort measure. It can be beneficial even in early stages of substance use disorder and helps prevent conditions from escalating.

- “MAT increases the risk of overdose.”

- Quite the opposite—MAT reduces overdose risk by preventing relapse and withdrawal, which are commonly tied to fatal overdoses.

By addressing these misconceptions, providers, patients, and communities can better understand that medication-assisted treatment is a safe, evidence-based intervention that improves recovery outcomes, reduces opioid overdose risk, and supports long-term stability.

Get Help For Yourself or A Loved One Today

Recovery may seem daunting, but effective help is available. Explore residential drug rehabs or specialized alcohol addiction treatment programs to find the right environment for healing. Use our free tool to search for addiction treatment by insurance, location, and amenities now.

FAQs

-

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK585210/

-

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK541393/

-

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459126/

-

https://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/products/retention-strategies-opioid-use-disorder/rapid-protocol

-

https://www.pew.org/en/research-and-analysis/fact-sheets/2016/11/medication-assisted-treatment-improves-outcomes-for-patients-with-opioid-use-disorder

-

https://www.hhs.gov/opioids/treatment/resources-opioid-treatment-providers/index.html

-

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534811/

-

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8905252/

-

https://www.samhsa.gov/substance-use/treatment/options/naltrexone

-

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459340/

-

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0087366&

-

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9179530/

-

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2811435?

-

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4014027/

-

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9175946/

-

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2117127/

-

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2528204/

-

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK615018/

-

https://www.thesun.ie/health/14741230/weight-loss-jab-cocaine-semaglutide-addiction/

-

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6751381/

-

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30724094/

-

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4133028/

Our Promise

How Is Recovery.com Different?

We believe everyone deserves access to accurate, unbiased information about mental health and recovery. That’s why we have a comprehensive set of treatment providers and don't charge for inclusion. Any center that meets our criteria can list for free. We do not and have never accepted fees for referring someone to a particular center. Providers who advertise with us must be verified by our Research Team and we clearly mark their status as advertisers.

Our goal is to help you choose the best path for your recovery. That begins with information you can trust.