Is Alcohol Bad for Your Brain? Understanding the Impact of Alcohol on Cognitive Health

Sarah holds a B.A. in Psychology from the University of Wisconsin-Madison where she was part of a psycho-social research lab. She is the Content Manager and Editor at Recovery.com, creating informational video resources on behavioral health.

Dr. Mala, is the Chief Clinical Officer at Recovery.com, where she develops impartial and informative resources for people seeking addiction and mental health treatment.

Sarah holds a B.A. in Psychology from the University of Wisconsin-Madison where she was part of a psycho-social research lab. She is the Content Manager and Editor at Recovery.com, creating informational video resources on behavioral health.

Dr. Mala, is the Chief Clinical Officer at Recovery.com, where she develops impartial and informative resources for people seeking addiction and mental health treatment.

- Alcohol can have significantly detrimental effects on the brain.

- Chronic drinking can lead to structural brain changes and lasting neurological issues.

- Seeking professional help is a crucial step towards regaining brain health.

Although drinking is commonly accepted in most cultures, alcohol can damage your brain more than you think. Alcohol affects brain function by interacting with neurotransmitter systems and altering the communication between nerve cells while depressing your nervous system, causing a slew of side effects, wanted or unwanted.

Short-Term Effects of Alcohol on the Brain

Alcohol impacts how your brain and body communicate soon after you take those first few sips. Short-term effects include:

Euphoria

Drinking alcohol causes euphoria, commonly referred to as a “buzz” or “high.” Alcohol activates the brain’s reward system and increases dopamine release.1 People may experience increased confidence and sociability, as well as decreased inhibition. They also feel less stressed and anxious. These feelings can be enjoyable and are why people choose to drink alcohol in the first place. However, it’s important to remember that alcohol can also cause feelings of depression, irritability, and aggression when consumed in excess.

Impaired Frontal Cortex

The frontal cortex is one of the most important areas of the brain, responsible for decision-making, planning, problem-solving, and regulating behavior. It’s no surprise that alcohol has a damaging effect on the communication between neurons in the frontal cortex.2 This can lead to difficulty making decisions, planning, and focusing. It can also impair the ability to control emotions and behavior, leading to impulsive and reckless decisions.

Impacts on the Central Nervous System

Alcohol’s impact on the central nervous system leads to slurred speech and a lack of coordination. And alcohol can impair memory storage, leading to difficulties remembering recent events or conversations.3 You could even experience a blackout, where you have no memory of the situation because the memories could not be stored in the hippocampus.

Long-Term Effects of Alcohol on the Brain

Day to day, it may be hard to notice how your drinking is affecting your brain and body. Over time, however, persistent heavy drinking leaves you susceptible to structural changes and damage in certain areas of the brain.4 Each drink can wreak havoc, physically and mentally. In a worst-case scenario, some of the destruction might not be reversible.

Physical Health Complications

One of the most well-known effects of excessive and long-term alcohol use is liver damage. Unfortunately, it can lead to a range of other health complications, such as heart diseases and pancreatitis, which can have serious and potentially life-threatening consequences. It’s essential to be aware of these issues and take steps to reduce your risk of damage to your body.

Weakened Immune System

Chronic alcohol consumption can significantly impair the body’s immune system, increasing the risk of developing illnesses and infections.5 When the immune system is weakened, it’s unable to function properly and fight off invading pathogens, leaving the body vulnerable to attack. Long-term alcohol use can also disrupt the body’s natural balance of hormones, which can further weaken the immune system.6 Poor nutrition and dehydration resulting from heavy drinking also weakens the immune system.

Premature Aging

Some studies emphasize the premature aging hypothesis, which states that heavy drinking accelerates natural chronological aging, beginning with the onset of problem drinking.7 This idea highlights how alcohol’s damaging effects can cause permanent changes and complications, such as cognitive decline and memory problems.

Sleep and Alcohol’s Effects on the Brain

Sleep is the basic building block on which you build a healthy life. As a depressant, alcohol is a sedative that interacts with several neurotransmitter systems involved in sleep regulation.8 Alcohol disrupts how your rapid eye movement (REM) cycle progresses throughout the night. Whenever your blood alcohol concentration (BAC) is highest, among other factors, determines how the cycle is disturbed. Without quality sleep, your mood and cognitive function can suffer. Chronic alcohol abuse can even spur sleep issues like insomnia.

Neurodegeneration

Alcohol’s neurotoxic effect on the brain can cause neuron destruction, also called neurodegeneration.9 Once your neurons and their pathways change, it’s difficult for your brain to properly communicate with itself and the body because neuron loss jeopardizes how neural networks function. Without healthy networks, your brain’s health can severely decline.

Alcohol Abuse and Brain Health

Research shows that people with alcoholism have smaller brain sizes compared to those who don’t.10 Long-term alcohol consumption can also lead to a decrease in gray matter and white matter in the frontal cortex.11 This might be because alcohol has neurotoxic effects on nerve cells, which can contribute to neuronal damage and increased vulnerability to alcohol-related brain damage (ARBD) like dementia.

While it is possible to develop a few different alcohol-related brain disorders, two of the most severe include Wernicke syndrome and Korsakoff syndrome. Both are associated with thiamine (vitamin B1) deficiency and alcohol abuse.12 Thiamine helps the brain turn sugar into energy. With thiamine deficiency, brain cells cannot generate enough energy to function properly, which causes a myriad of physical and mental difficulties.

Wernicke Syndrome

Alcohol’s destruction to neurons and cell communication in the peripheral and central nervous systems can prompt the onset of Wernicke syndrome. Wernicke’s encephalopathy can have a severe and sudden onset and involves ophthalmoplegia, which is paralysis or weakness of eye muscles.13 It also includes ataxia, weakened muscle control in their arms and legs, and confusion. Wernicke’s encephalopathy usually precedes the onset of Korsakoff syndrome.14

Korsakoff Syndrome

Alcohol abuse can inhibit learning new information, remembering recent events, and long-term memory processing. Over enough time, this can progress into Korsakoff syndrome. Korsakoff’s psychosis causes damage to the brain’s thalamus and hypothalamus, which can lead to confusion, memory problems, coma, and irreversible brain damage.14

If you or someone you know is experiencing these symptoms, visit your primary care practitioner immediately. If the situation feels life-threatening, call 911 and/or take them to an emergency room and stay with them until they have medical help. If you live outside of the United States, you can find your country’s emergency number in this list.15

Neurotransmitter Disruptions

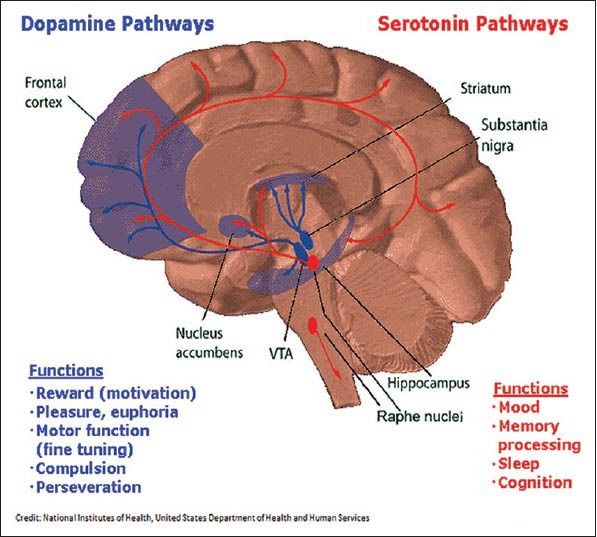

Alcohol primarily interacts with the reward and stress systems in the brain, which includes dopaminergic, serotoninergic, glutamatergic and GABAergic neural circuits.16 A neural circuit has a series of neurons that send chemical signals to one another.

As you drink, your brain releases more dopamine, endorphins, and serotonin and suppresses Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid (GABA) and glutamate release. These disruptions in normal functioning greatly affect your mood, behavior, and cognition.

Alcohol’s impact on dopamine levels is a key factor in the formation of alcohol dependence.17 Dopamine is not only the “feel good” hormone, but it’s also the motivation and incentive-based hormone. Your brain begins to reinforce unhealthy drinking habits because your dopamine levels rise when consuming alcohol, so, without alcohol, your brain will begin to crave that dopamine boost again. This spurs the dangerous cycle of chasing the high.

Image from the Indian Journal of Human Genetics16

Mental Health and Alcohol

Alcohol and mental health are closely intertwined, and the relationship between the two is complex. Some people are more vulnerable to alcohol abuse because of preexisting conditions. In contrast to those who drink responsibly or abstain, those who abuse alcohol—especially adolescents and those with long-term exposure—are more likely to develop depression or other psychological conditions.

The prevalence of anxiety, depression, and other mental disorders is significantly higher among those with alcoholism compared to the general population.18 For many, this is due to using alcohol as self-medication for the uncomfortable emotions associated with these mental disorders. Chemical changes in the brain from alcohol, such as the disruption of neurotransmitters crucial in maintaining good mental health, also contribute to and worsen existing symptoms.

If you have co-occurring disorders, finding specialized care for all conditions is essential because of their complicated relationship. You’re actually more likely to recover from each condition if the alcoholism and the co-occurring mental health disorder(s) are individually addressed and treated.18 Explore professional treatment options with your doctor to get to the root cause of your co-occurring disorders.

Adolescents’ Vulnerability to Alcohol’s Effects

According to the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, roughly 35% of adolescents (ages 12-20) have tried alcohol.19 And this number likely doesn’t include the many teens who didn’t report their drinking. Alcohol use during these crucial years can disrupt normal brain maturation and increase the risk of cognitive impairments because of restricted blood flow in certain brain regions and electrical activity.20

Adolescents are also more prone to risk-taking behaviors, which drinking only exacerbates.21 Alcohol greatly affects the prefrontal cortex, which is the decision-making area in the brain that is still developing for adolescents. They could be more likely to make bad decisions and get into trouble if they’re drinking, such as getting into a car crash while driving under the influence.

If your child is in these pivotal years, have an open conversation with them. Being open-minded and honest with them, and actively listening to their experiences without judgment, will create trust. Your child may be more likely to listen to your advice if you approach these conversations with empathy and the desire to learn from each other.

Can the Brain Recover?

So, is it possible for your brain to recover from alcohol’s damage? In many cases, the answer is yes. It is a resilient organ that can heal. Your brain has something called neuroplasticity, which means your nervous system can change, positively or negatively, to stimuli.22 So, while your neuroplasticity can negatively change from alcohol abuse, it can also positively adapt in recovery.

Recovery from alcohol abuse is complex, and it can vary depending on factors like genetics, age, and overall health. The best way to recover is to stop drinking; however, this should be done over time with a tapering plan. Attempting to stop drinking “cold turkey” is dangerous and could cause serious implications.

For this reason, recovering with professional guidance is essential. Medical professionals can ensure that the detoxing process goes as smoothly as possible. And tapering off alcohol will decrease the likelihood of withdrawal symptoms.

Alcohol shouldn’t be running your life. Your health matters. Begin your journey towards sobriety today by browsing rehabs that specialize in alcohol treatment.

There Is Hope for Recovery

Addiction is treatable, and a life of freedom is possible. Connect with drug and alcohol treatment centers that specialize in your specific needs, from holistic care to medication-assisted treatment. Don’t wait another day to get help; find a recovery program that works for you.

FAQs

-

MA, H., & ZHU, G. (2014). The dopamine system and alcohol dependence. Shanghai Archives of Psychiatry, 26(2), 61–68. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4120286/

-

Abernathy, K., Chandler, L. J., & Woodward, J. J. (2010). Alcohol and the prefrontal cortex. In International Review of Neurobiology (Vol. 91, pp. 289–320). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0074-7742(10)91009-X

-

White, A. M. (2003). What happened? Alcohol, memory blackouts, and the brain. Alcohol Research & Health, 27(2), 186–196. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6668891/

-

Harper, C., & Matsumoto, I. (2005). Ethanol and brain damage. Current Opinion in Pharmacology, 5(1), 73–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coph.2004.06.011

-

Sarkar, D., Jung, M. K., & Wang, H. J. (2015). Alcohol and the immune system. Alcohol Research : Current Reviews, 37(2), 153–155. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4590612/

-

Rachdaoui, N., & Sarkar, D. K. (2017). Pathophysiology of the effects of alcohol abuse on the endocrine system. Alcohol Research : Current Reviews, 38(2), 255–276. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5513689/

-

Oscar-Berman, M., & Marinkovic, K. (2003). Alcoholism and the brain: An overview. Alcohol Research & Health, 27(2), 125–133. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6668884/

-

Colrain, I. M., Nicholas, C. L., & Baker, F. C. (2014). Alcohol and the sleeping brain. In Handbook of Clinical Neurology (Vol. 125, pp. 415–431). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-62619-6.00024-0

-

Tateno, M., & Saito, T. (2008). Biological studies on alcohol-induced neuronal damage. Psychiatry Investigation, 5(1), 21–27. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2796092/

-

Crews, F. T. (2008). Alcohol-related neurodegeneration and recovery. Alcohol Research & Health, 31(4), 377–388. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3860462/

-

Daviet, R., Aydogan, G., Jagannathan, K., Spilka, N., Koellinger, P. D., Kranzler, H. R., Nave, G., & Wetherill, R. R. (2022). Associations between alcohol consumption and gray and white matter volumes in the UK Biobank. Nature Communications, 13(1), 1175. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35246521/

-

Wernicke-korsakoff syndrome. (n.d.). National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Retrieved September 19, 2023, from https://www.ninds.nih.gov/health-information/disorders/wernicke-korsakoff-syndrome

-

Vasan, S., & Kumar, A. (2023). Wernicke encephalopathy. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470344/

-

Korsakoff Syndrome. (n.d.). Alz.Org; Alzheimer’s Association. https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/what-is-dementia/types-of-dementia/korsakoff-syndrome

-

List of emergency telephone numbers. (2023). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_emergency_telephone_numbers

-

Banerjee, N. (2014). Neurotransmitters in alcoholism: A review of neurobiological and genetic studies. Indian Journal of Human Genetics, 20(1), 20–31. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4065474/

-

Di Chiara, G. (1997). Alcohol and dopamine. Alcohol Health and Research World, 21(2), 108–114. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6826820/

-

Mental Health Issues: Alcohol Use Disorder and Common Co-occurring Conditions. (n.d.). National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/health-professionals-communities/core-resource-on-alcohol/mental-health-issues-alcohol-use-disorder-and-common-co-occurring-conditions

-

Underage drinking in the united states (Ages 12 to 20) | national institute on alcohol abuse and alcoholism(Niaaa). (n.d.). Retrieved September 19, 2023, from https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohols-effects-health/alcohol-topics/alcohol-facts-and-statistics/underage-drinking-united-states-ages-12-20

-

Tapert, S. F., Caldwell, L., & Burke, C. (2004). Alcohol and the adolescent brain. Alcohol Research & Health, 28(4), 205–212. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6601673/

-

Steinberg, L. (2008). A social neuroscience perspective on adolescent risk-taking. Developmental Review : DR, 28(1), 78–106. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2396566/

-

Seo, D., & Sinha, R. (2015). Neuroplasticity and predictors of alcohol recovery. Alcohol Research : Current Reviews, 37(1), 143–152. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4476600/

Our Promise

How Is Recovery.com Different?

We believe everyone deserves access to accurate, unbiased information about mental health and recovery. That’s why we have a comprehensive set of treatment providers and don't charge for inclusion. Any center that meets our criteria can list for free. We do not and have never accepted fees for referring someone to a particular center. Providers who advertise with us must be verified by our Research Team and we clearly mark their status as advertisers.

Our goal is to help you choose the best path for your recovery. That begins with information you can trust.