Ecopsychology: 5 Science-Backed Benefits of Nature Therapy for Mental Health

Hannah is a holistic wellness writer who explores post-traumatic growth and the mind-body connection through her work for various health and wellness platforms. She is also a licensed massage therapist who has contributed meditations, essays, and blog posts to apps and websites focused on mental health and fitness.

Dr. Mala, is the Chief Clinical Officer at Recovery.com, where she develops impartial and informative resources for people seeking addiction and mental health treatment.

Hannah is a holistic wellness writer who explores post-traumatic growth and the mind-body connection through her work for various health and wellness platforms. She is also a licensed massage therapist who has contributed meditations, essays, and blog posts to apps and websites focused on mental health and fitness.

Dr. Mala, is the Chief Clinical Officer at Recovery.com, where she develops impartial and informative resources for people seeking addiction and mental health treatment.

Have you ever noticed how a walk in the park can shift your entire mood, or how sitting by a lake helps quiet racing thoughts? You’re not imagining it. Spending time in natural environments makes people a lot more likely to report feeling better mentally and emotionally.

This isn’t just feel-good advice. It’s the foundation of ecopsychology, a field that explores how our connection to the natural world directly impacts our mental and emotional health. In this guide, you’ll discover what ecopsychology is, how it works, and the proven ways it can transform your healing journey.

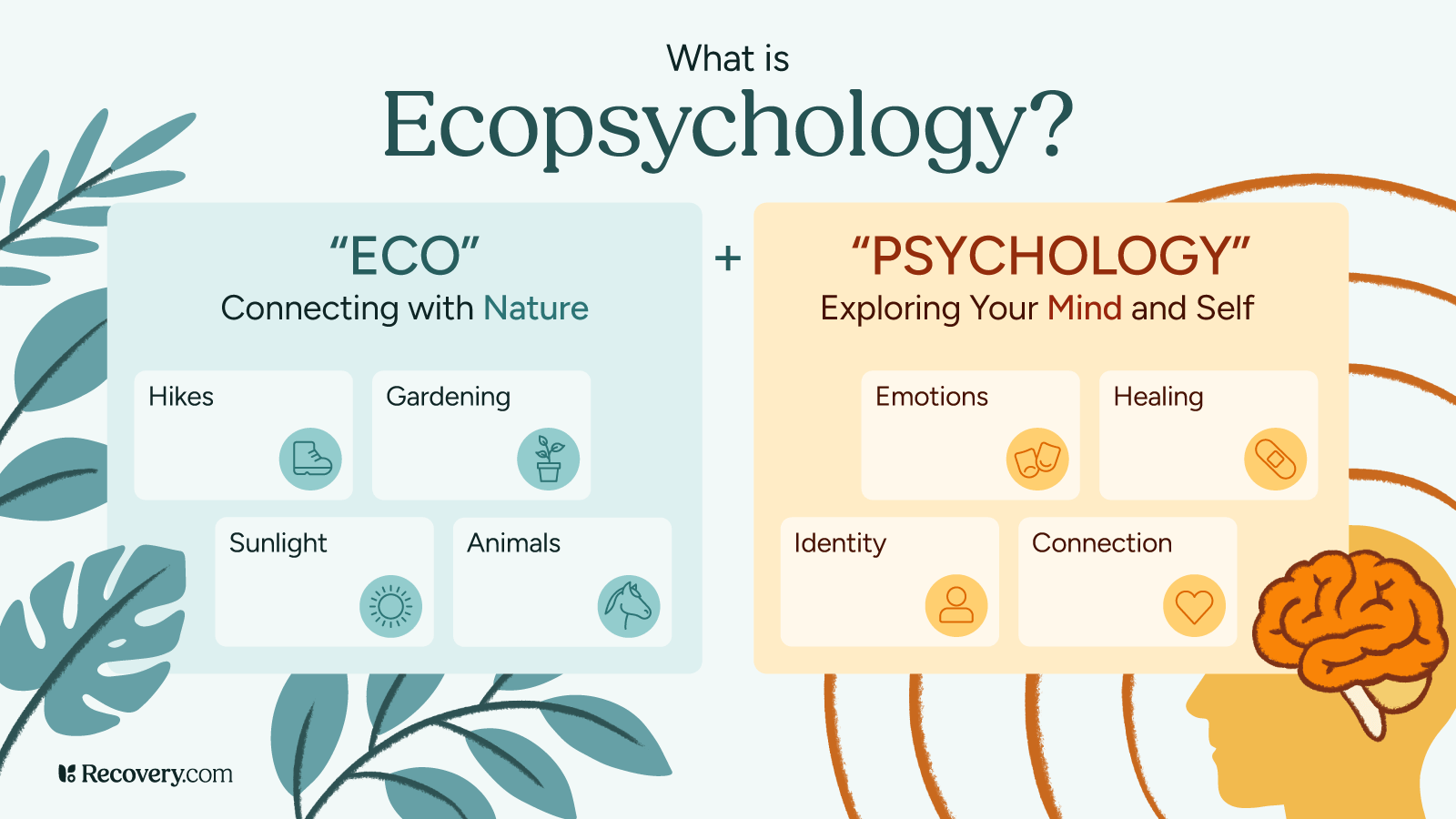

What Is Ecopsychology?

The field of ecopsychology recognizes something many of us intuitively know: humans aren’t separate from nature, but deeply interconnected with it. When this connection is strong, we thrive. When it’s broken, we may struggle with anxiety, depression, and a sense of disconnection.

Ecopsychology studies how nature impacts your physical, mental, and emotional health.1 This field emerged in the 1960s and gained momentum when psychologist Theodore Roszak coined the term in his 1992 book The Voice of the Earth.2 Roszak believed that conventional psychology was missing a critical piece: the human-nature relationship.3

Ecopsychology differs from traditional psychotherapy by viewing your well-being through an environmental lens. This takes into account the experience that cultural ecologist and geophilosopher David Abram calls “being human in a more-than-human world.”4

Unlike talk therapy, it doesn’t just focus on your inner thought processes and resulting behaviors. It also considers how your connection to nature affects human health. The field is built on the understanding that humans evolved in natural environments and that disconnection from nature can contribute to psychological distress.5

The Theory Behind Ecopsychology

Ecopsychology is based on a few key concepts. The first is what Roszak called the “ecological unconscious“—a core part of human identity that’s deeply tied to the ecosystems of the natural world.6 This theory suggests you’re born with an innate connection to nature that influences your psychological well-being.

Another important concept is biopilia, introduced by biologist Edward Wilson. This theory proposes that humans have an instinctive bond with other living systems.7 When you feel calmer around plants or energized by ocean waves, you’re experiencing biophilia in action.

Research supports these theories. Studies show that nature exposure activates your parasympathetic nervous system, which reduces stress hormones and makes you feel calmer.8 Even just looking at green scenery can lower blood pressure and improve your mood within minutes.

What Does an Ecopsychologist Do?

Ecopsychologists are mental health professionals who integrate nature-based approaches into their practice.9 They usually hold degrees in psychology, counseling, or social work, plus specialized training in nature-based interventions.

These practitioners might conduct therapy sessions outdoors, use natural metaphors in treatment, or prescribe specific nature activities as part of your healing process. Some ecopsychologists specialize in wilderness therapy, leading multi-day outdoor experiences that combine traditional therapy with adventure activities.

Unlike traditional therapists who work mainly in office settings, ecopsychologists view the natural environment as a co-therapist. They might guide you through mindful nature walks, help you process emotions while gardening, or use animal-assisted therapy to build connection and trust.

Who Can Benefit from Ecopsychology?

Ecopsychology can be helpful if you’re dealing with mental stress from anxiety, depression, trauma, or substance use disorders.10 Many people in recovery find that nature-based approaches are a great complement to conventional treatments as they reduce stress and make for a more enjoyable recovery experience.

You might especially benefit from ecopsychology if you feel disconnected from yourself or others, struggle with urban stress, or find that indoor environments feel overwhelming.11 Immersion in nature can bring a sense of calm and improve focus for people with ADHD. People dealing with grief, major life transitions, or chronic stress might also find that natural settings provide some much-needed comfort and perspective.

Ecopsychology can also be valuable if you’re interested in holistic approaches to mental health care that address mind, body, and spirit together. And you don’t have to choose between approaches—it works well alongside medication, talk therapy, and other evidence-based treatments.

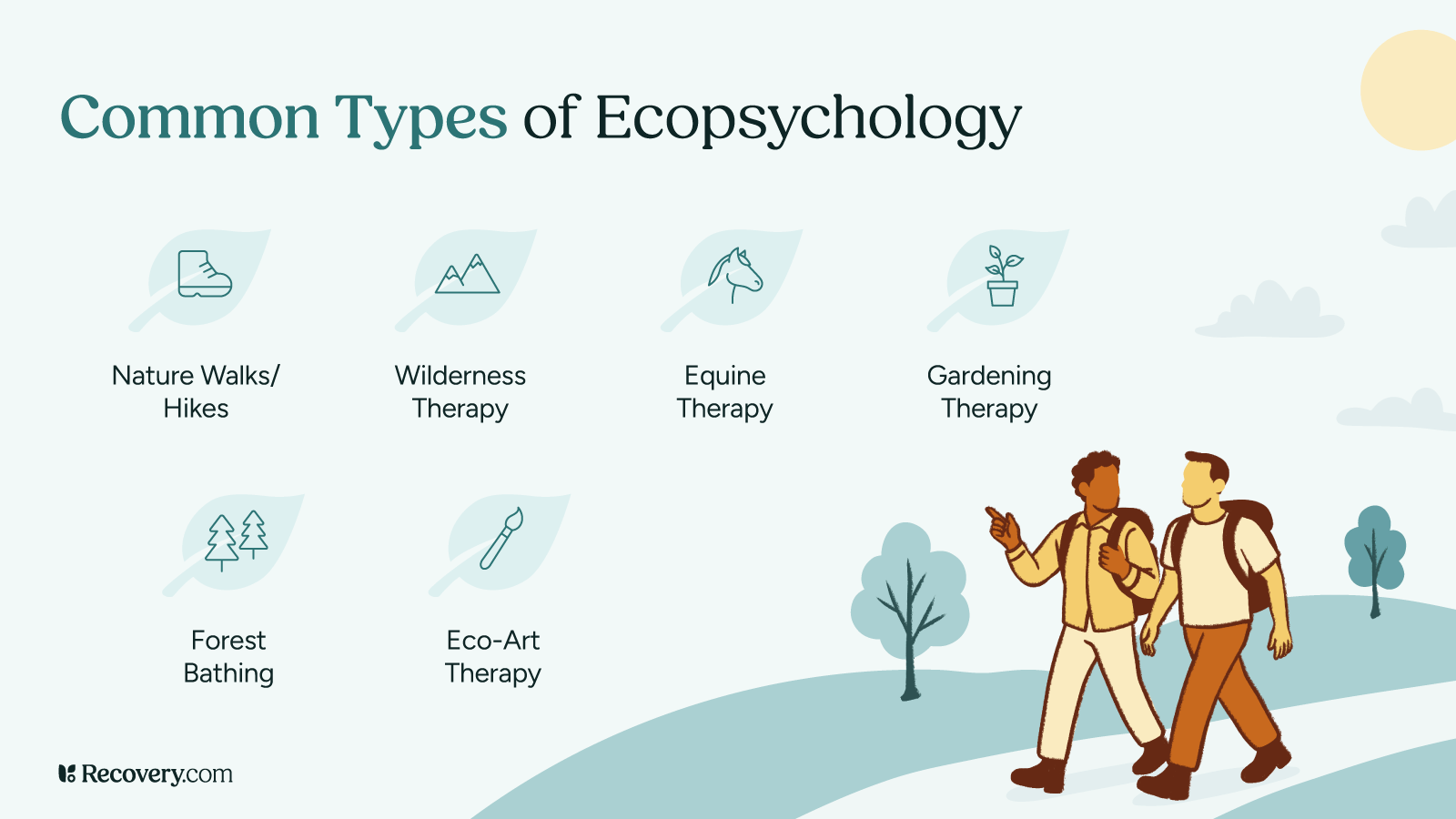

Types of Eco-Therapies Available

Nature-based therapy takes many forms; each offers unique benefits for your mental health recovery:

- Wilderness therapy involves multi-day outdoor experiences that combine traditional therapy with adventure activities like hiking or rock climbing. These programs help you build confidence, process trauma, and develop coping skills in challenging but supportive environments.

- Horticultural therapy uses gardening and plant-related activities to promote healing. Working with plants can reduce anxiety, improve focus, and provide a sense of connectedness. This can look like planting seeds, tending vegetables, creating floral arrangements, and more.

- Animal-assisted therapy incorporates interactions with trained animals into treatment. Horses, dogs, and other animals can help you develop trust, practice communication skills, and experience unconditional acceptance.

- Adventure therapy combines outdoor activities with therapeutic processing. Activities like kayaking, hiking, or team-building exercises create opportunities for personal growth and relationship building.

- Forest bathing or “shinrin-yoku” involves mindfully immersing yourself in forest settings.12 Originally developed in Japan, this experiential therapy involves relating to nature not just as a backdrop for achieving goals like exercise, but as an opportunity to engage all your senses to connect with the natural world.

Mental Health Benefits of Ecopsychology

Research shows that ecopsychology can improve your mental health in several ways:

1. Stress Reduction

This is perhaps the most immediate benefit. Natural environments lower cortisol levels and activate your body’s relaxation response.13 Even brief nature exposure can reduce stress more effectively than urban environments.

2. Improved Mood and Reduced Anxiety

Immersion in nature increases your production of serotonin, the neurotransmitter linked to happiness and well-being.14 Research shows that spending time in green spaces can reduce symptoms of depression and anxiety within weeks.15

3. Enhanced Focus and Cognitive Function

Theseresult from what researchers call “attention restoration.”16 Natural environments give your you room to breathe and take a break from the constant stimulation of modern life. This, in turn, improves your ability to concentrate and make decisions.

4. Better Emotional Regulation

This develops through nature’s calming influence on your nervous system. Regular nature exposure can help you manage difficult emotions and respond to stress with greater resilience.

5. A More Positive Perspective

Increased self-esteem and sense of purpose often emerge from reconnecting with something larger than yourself.17 Nature experiences can provide perspective on personal problems while inspiring awe and gratitude.

Addressing Climate Anxiety and Eco-Grief

Climate anxiety—worry about environmental problems and climate change—affects millions of people worldwide.18 Ecopsychology validates these concerns as natural responses to real environmental threats.

Rather than avoiding these feelings, ecopsychology encourages you to process eco-grief—the sadness about environmental loss—in healthy ways.19 This might involve connecting with others who share your concerns, engaging in environmental education, activism, and sustainability, or finding hope through positive actions.

Many people find that spending time in nature, even while grieving environmental losses, provides comfort and motivation to take action. Recognizing that caring for yourself and caring for the planet are interconnected goals can help us make sense of suffering in a tech-centered world.20

As author and scholar of deep ecology Joanna Macy, Ph.D says of the natural world’s role in human health.21

I love this world. And the world loves you back. There’s this reciprocity.

Engaging in ecotherapy can be a way to start noticing more of that natural reciprocity and abundance in your life.

Get Help For Yourself or A Loved One Today

Recovery may seem daunting, but effective help is available. Explore residential drug rehabs or specialized alcohol addiction treatment programs to find the right environment for healing. Use our free tool to search for addiction treatment by insurance, location, and amenities now.

FAQs

-

Thoma, M. V., Rohleder, N., & Rohner, S. L. (2021). Clinical Ecopsychology: The Mental Health Impacts and Underlying Pathways of the Climate and Environmental Crisis. Frontiers in psychiatry, 12, 675936. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.675936

-

Roszak, T. (1992). The voice of the Earth. Simon & Schuster.

-

Kanner, A. D. (2014). Ecopsychology's home: The interplay of structure and person. Ecopsychology, 6(2). https://doi.org/10.1089/eco.2014.0022

-

Abram, D. (n.d.). On being human in a more-than-human world. Center for Humans and Nature. https://humansandnature.org/to-be-human-david-abram/

-

Beery, T., Olafsson, A. S., Gentin, S., Maurer, M., Stålhammar, S., Albert, C., Bieling, C., Buijs, A., Fagerholm, N., Garcia-Martin, M., … & Williams, K. (2023). Disconnection from nature: Expanding our understanding of human–nature relations. People and Nature, 5(2), 302–314. https://doi.org/10.1002/pan3.10451

-

Binghamton University. (n.d.). Ecopsychology justification. Nature Preserve. https://www.binghamton.edu/nature-preserve/about/justification/ecopsychology.html

-

Grinde, B., & Patil, G. G. (2009). Biophilia: Does Visual Contact with Nature Impact on Health and Well-Being? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 6(9), 2332-2343. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph6092332

-

Van den Berg, M. M. H. E., Maas, J., Muller, R., Braun, A., Kaandorp, W., Van Lien, R., Van Poppel, M. N. M., Van Mechelen, W., & Van den Berg, A. E. (2015). Autonomic nervous system responses to viewing green and built settings: Differentiating between sympathetic and parasympathetic activity. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 12(12), 15860–15874. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph121215026

-

Auckerman, N. B. (2022). Ecopsychologists’ Vital Importance in the Time of Climate Crises (Doctoral dissertation, Antioch University, Santa Barbara). Open access at Antioch University AURA and the OhioLINK ETD Center

-

Buzzell, L., & Chalquist, C. (Eds.). (2009). Ecotherapy: Healing with nature in mind. Sierra Club Books.

-

Hernandez, D. C., Daundasekara, S. S., Zvolensky, M. J., Reitzel, L. R., Maria, D. S., Alexander, A. C., Kendzor, D. E., & Businelle, M. S. (2020). Urban Stress Indirectly Influences Psychological Symptoms through Its Association with Distress Tolerance and Perceived Social Support among Adults Experiencing Homelessness. International journal of environmental research and public health, 17(15), 5301. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17155301

-

Wen, Y., Yan, Q., Pan, Y., Gu, X., & Liu, Y. (2019). Medical empirical research on forest bathing (Shinrin-yoku): A systematic review. Environmental Health and Preventive Medicine, 24, Article 70. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12199-019-0822-8

-

Ewert, A., & Chang, Y. (2018). Levels of nature and stress response. Behavioral Sciences, 8(5), 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs8050049

-

Selhub, E. M., & Logan, A. C. (2012). Your brain on nature: The science of nature's influence on your health, happiness and vitality. Wiley.

-

Liu, Z., Chen, X., Cui, H., Ma, Y., Gao, N., Li, X., Meng, X., Lin, H., Abudou, H., Guo, L., & Liu, Q. (2023). Green space exposure on depression and anxiety outcomes: A meta-analysis. Environmental Research, 231(Part 3), Article 116303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2023.116303

-

Ohly, H., White, M. P., Wheeler, B. W., Bethel, A., Ukoumunne, O. C., & Nikolaou, V. (2016). Attention Restoration Theory: A systematic review of the attention restoration potential of exposure to natural environments. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 48, 305–343. https://doi.org/10.1080/10937404.2016.1196155

-

Softas-Nall, S., & Woody, W. D. (2017). The loss of human connection to nature: Revitalizing selfhood and meaning in life through the ideas of Rollo May. Ecopsychology, 9(4), 277–285. https://doi.org/10.1089/eco.2017.0020

-

Ojala, M., Cunsolo, A., Ogunbode, C. A., & Middleton, J. (2021). Anxiety, worry, and grief in a time of environmental and climate crisis: A narrative review. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 46, 35–58. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-012220-022716

-

Pihkala, P. (2022). The process of eco-anxiety and ecological grief: A narrative review and a new proposal. Sustainability, 14(24), 16628. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416628

-

Fisher, A. (2013). Radical ecopsychology: Psychology in the service of life (2nd ed.). SUNY Press.

-

Herman, D. F. (n.d.). Joanna Macy, PhD: The tireless voice of a wise elder activist. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5bb69eb0fb18206bfc832a6b/t/5e62d0293f5dd44f5d0c5e6b/1583534126857/JHHE_JMarticle-2020.pdf

Our Promise

How Is Recovery.com Different?

We believe everyone deserves access to accurate, unbiased information about mental health and recovery. That’s why we have a comprehensive set of treatment providers and don't charge for inclusion. Any center that meets our criteria can list for free. We do not and have never accepted fees for referring someone to a particular center. Providers who advertise with us must be verified by our Research Team and we clearly mark their status as advertisers.

Our goal is to help you choose the best path for your recovery. That begins with information you can trust.