Anorexia vs. Bulimia: Knowing These 4 Key Differences Can Improve Your Recovery

Hannah is a holistic wellness writer who explores post-traumatic growth and the mind-body connection through her work for various health and wellness platforms. She is also a licensed massage therapist who has contributed meditations, essays, and blog posts to apps and websites focused on mental health and fitness.

Dr. Mala, is the Chief Clinical Officer at Recovery.com, where she develops impartial and informative resources for people seeking addiction and mental health treatment.

Hannah is a holistic wellness writer who explores post-traumatic growth and the mind-body connection through her work for various health and wellness platforms. She is also a licensed massage therapist who has contributed meditations, essays, and blog posts to apps and websites focused on mental health and fitness.

Dr. Mala, is the Chief Clinical Officer at Recovery.com, where she develops impartial and informative resources for people seeking addiction and mental health treatment.

You might think anorexia and bulimia are basically the same thing, but actually, they work in very different ways. Learning about these differences isn’t just about knowing medical facts—it can help you spot warning signs in yourself or someone you care about.

Let’s look at how anorexia and bulimia compare and what physical signs, behaviors, thinking patterns, and health risks are unique to each condition. We’ll also explain treatment options and where to find help, whether you’re trying to understand your own experiences or are concerned about a loved one.

Before getting into the specific differences between anorexia and bulimia, what exactly is an eating disorder, and what makes them so serious?

What Are Eating Disorders?

Eating disorders are serious mental health conditions that involve harmful eating habits and troubling thoughts about food and eating, as well as distorted body image. About 9% of people in the U.S. will have an eating disorder in their lifetime.1 Women and girls are diagnosed more often, but anyone can develop these conditions.

Anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa are two of the most well-known eating disorders. They share some features but work differently in terms of eating behaviors, symptoms, and health effects. Other types include binge eating disorder and avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID).

Eating disorders aren’t choices or phases—they’re complex conditions influenced by genes, biology, psychology, and social factors. They can seriously harm people’s physical health, emotional well-being, and everyday life. But with quality treatment and support, people can and do recover—though that journey looks different for each person.

Anorexia Nervosa: Key Characteristics

Anorexia involves severely limiting food and having an intense fear of gaining weight, even when you’re already underweight. People with anorexia usually see their bodies differently than others do. For example, they may think they look fat even when they’re actually very thin.

According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5-TR), to be diagnosed with anorexia, someone must eat so little that they’re at an unusually low weight, be terrified of gaining weight, and have a distorted view of their body.2 There are two main types: The restricting type (mostly limiting food) and the binge-eating/purging type (restricting but sometimes also bingeing and purging).

Physical signs of anorexia include:3

- Extreme weight loss.

- Always feeling tired or dizzy.

- Complaining about being cold all the time.

- Development of fine hair all over your body.

- Constipation.

- Brittle nails.

- Dry skin.

- Stopped menstruation.

Many people who struggle with anorexia create strict food rules, like cutting food into tiny pieces, only eating at certain times, or avoiding meals with others.

The mental side often includes:

- Constantly thinking about food, calories, and weight.

- Feeling a sense of control or achievement when restricting food.

- Difficulty recognizing how serious your condition is.

- Reluctance to ask for help.

How can clinicians better identify bulimia given its “hidden” nature compared to the more visible signs of anorexia?

Being direct and sensitive when asking about binging or purging is important. It can be easy to dance around the topic, but it’s important to bring light to it in sessions so clients can be challenged. There is a delicate line to balance here, and it can be managed with tone, building trust, and appropriate timing. Clinicians can also ask about their recent diet history and exercise patterns. This may not directly or completely uncover behaviors, but it can be a leading indicator of areas where there may be some concerns.

Silvi Saxena, MBA, MSW, LSW, CCTP, OSW-C

Bulimia Nervosa: Key Characteristics

Bulimia involves cycles of eating huge amounts of food (binging) and then trying to prevent weight gain through behaviors like throwing up. During binges, someone eats an excessive amount of food in a short window and feels like they can’t stop or control their eating.

After binging, people with bulimia try to “undo” the calories they ate by making themselves throw up, taking laxatives or diuretics, fasting, or exercising too much. Unlike people with anorexia, those with bulimia usually stay at a normal weight or slightly above, which makes the condition a lot harder for others to notice.

Physical signs of bulimia might include:4

- Puffy cheeks.

- Dental problems from stomach acid.

- Calluses on knuckles from self-induced vomiting.

- Weight that fluctuates up and down.

- Stomach problems.

- Imbalanced electrolytes.

- Acid reflux.

- Chronic sore throats.

- Heartburn.

The binge-purge cycle often happens in secret and makes people feel disgusted, guilty, or ashamed. Despite these negative feelings, the cycle is hard to break because both binging and purging can temporarily make emotional pain feel better. Like anorexia, bulimia involves intense worry about body shape and weight, but the approach to food is very different.

Major Differences Between Anorexia and Bulimia

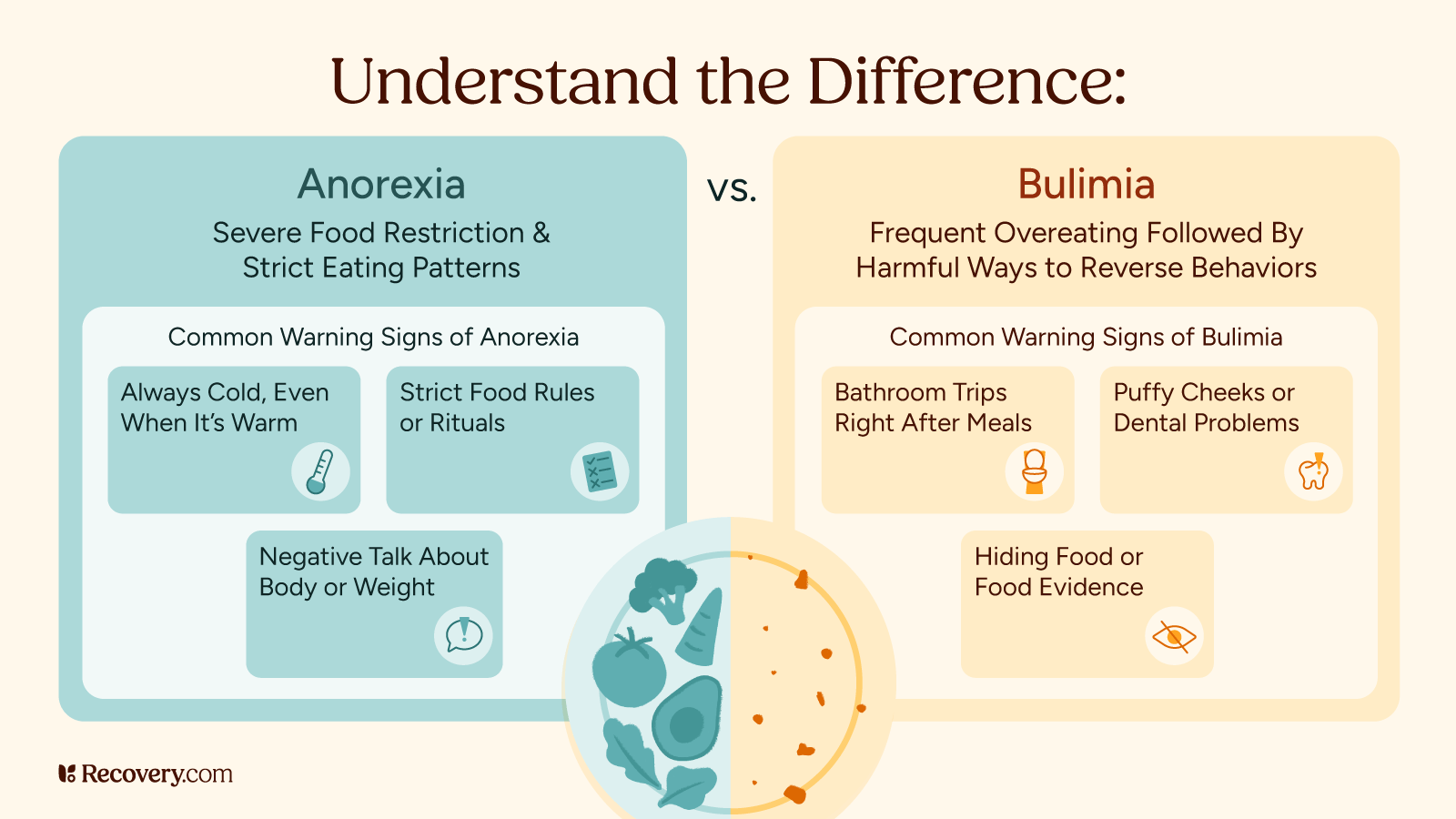

Physical Appearance

The most obvious difference is how people with these disorders typically look. Those with anorexia are usually very underweight, while people with bulimia may maintain their normal weight or be slightly overweight. This means you can often see anorexia, while bulimia can stay hidden for years.

Eating Patterns

The eating patterns are also quite different. People with anorexia mainly restrict their food intake, eating very little or avoiding certain foods completely.5 People with bulimia swing between episodes of binge eating (eating large amounts of food at a time) and compensatory behaviors to try to get rid of those calories.

Relationship to Food

These conditions cause different feelings about food, too. People with anorexia tend to create strict rules about food and may feel anxious about eating. Those with bulimia typically feel out of control during binges, often eating foods they normally avoid, then desperately trying to counteract what they’ve eaten.

Emotional Experience

The emotional experience is different as well. Anorexia often brings a sense of accomplishment from restricting food and losing weight, while bulimia usually involves intense shame around binging and purging.

Binge eating disorder (BED) and orthorexia survivor Elisa Aas describes how shame fueled the cycles of her disordered eating:6

You feel you abused food and your body so much you don’t deserve to enjoy food again.

Both of these conditions make people feel unhappy with their bodies, but how that shows up in behaviors is quite different.

Finding and diagnosing these disorders also follows different paths. Anorexia tends to be diagnosed earlier on because of visible weight loss, while bulimia’s secretive nature and normal-looking weight make it harder to notice from the outside.7 This difference can affect how quickly someone gets help, and what kind of help they need.

Key Similarities Between Anorexia and Bulimia

Though they may look different, anorexia and bulimia have important similarities. Both involve judging your self-worth largely based on your weight and body type. People with either condition often measure their value as a person by how they look or how well they can control their eating.8

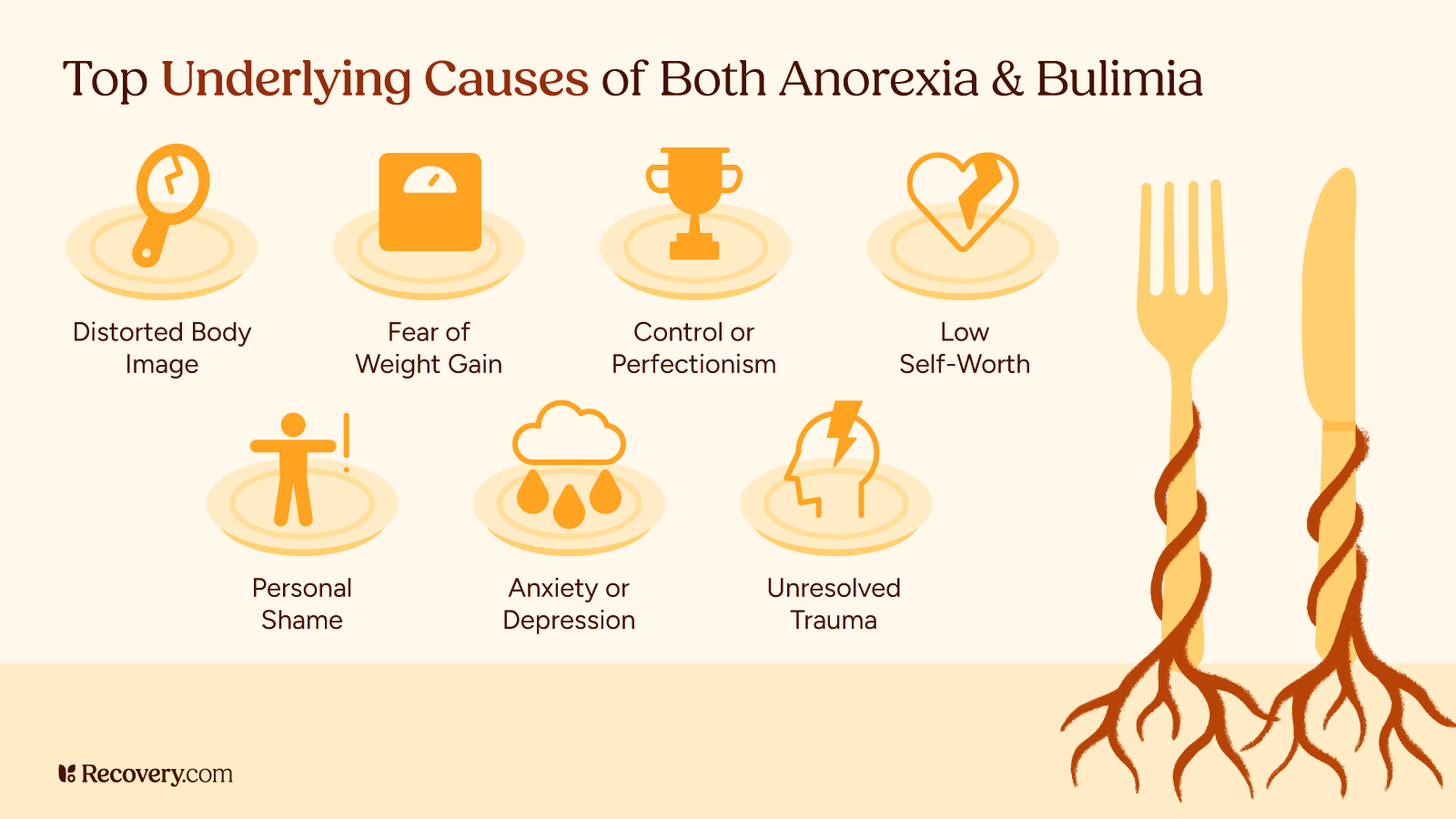

Risk Factors

Both anorexia and bulimia can come from similar risk factors, including genetics, personality traits like perfectionism, history of dieting, and cultural pressures around thinness.9 Traumatic experiences, family dynamics, and other mental health issues like anxiety or depression can contribute to both disorders.

What are the most promising developments in eating disorder treatment that address both the physical and psychological aspects of these conditions?

The most promising development I have seen in eating disorder treatment for Anorexia and Bulimia is the increase in adoption of the Health at Every Size Approach. So often, patients living in larger bodies have fallen by the wayside due to the stereotypes of what an eating disorder ‘should look like,’ when eating disorders are, first and foremost, mental illnesses that have a physical impact.

By treating the physical impacts of the disorder but not using them to determine the severity of one patient’s condition over another, and incorporating a variety of therapies (such as DBT, ACT, CBT, and family therapy), eating disorders are being treated at all angles. As a person in recovery who has lived in a larger body for most of my life, paired with my professional experience, I have witnessed how the Health at Every Size Approach leads to creating more inclusive treatment plans and lasting positive outcomes.

Sage Nestler, MSW | Releasing the Phoenix

Coping Mechanisms

There’s significant overlap between eating disorders, especially among people with anorexia.10 One study found that of the participants with anorexia, over half switched between the restricting and binge-eating/purging, and one-third developed bulimia. But interestingly, people initially diagnosed with bulimia nervosa rarely developed anorexia. So while diagnostic crossover is common in eating disorders, it tends to follow specific patterns.

Both of these sets of behaviors serve as strategies for coping with difficult emotions and life stress. Behaviors like restricting food or binge-purge cycles temporarily relieve anxiety, distress, or emptiness. That emotional relief and sense of control make both conditions very hard to overcome without addressing the underlying psychological needs they’re meeting.11

Impacts on People’s Lives

Finally, both of these common eating disorders seriously impact people’s quality of life, causing distress and making it hard to function at work or in social settings. They isolate people from their support networks at a time when they need connection the most.

Health Risks and Complications

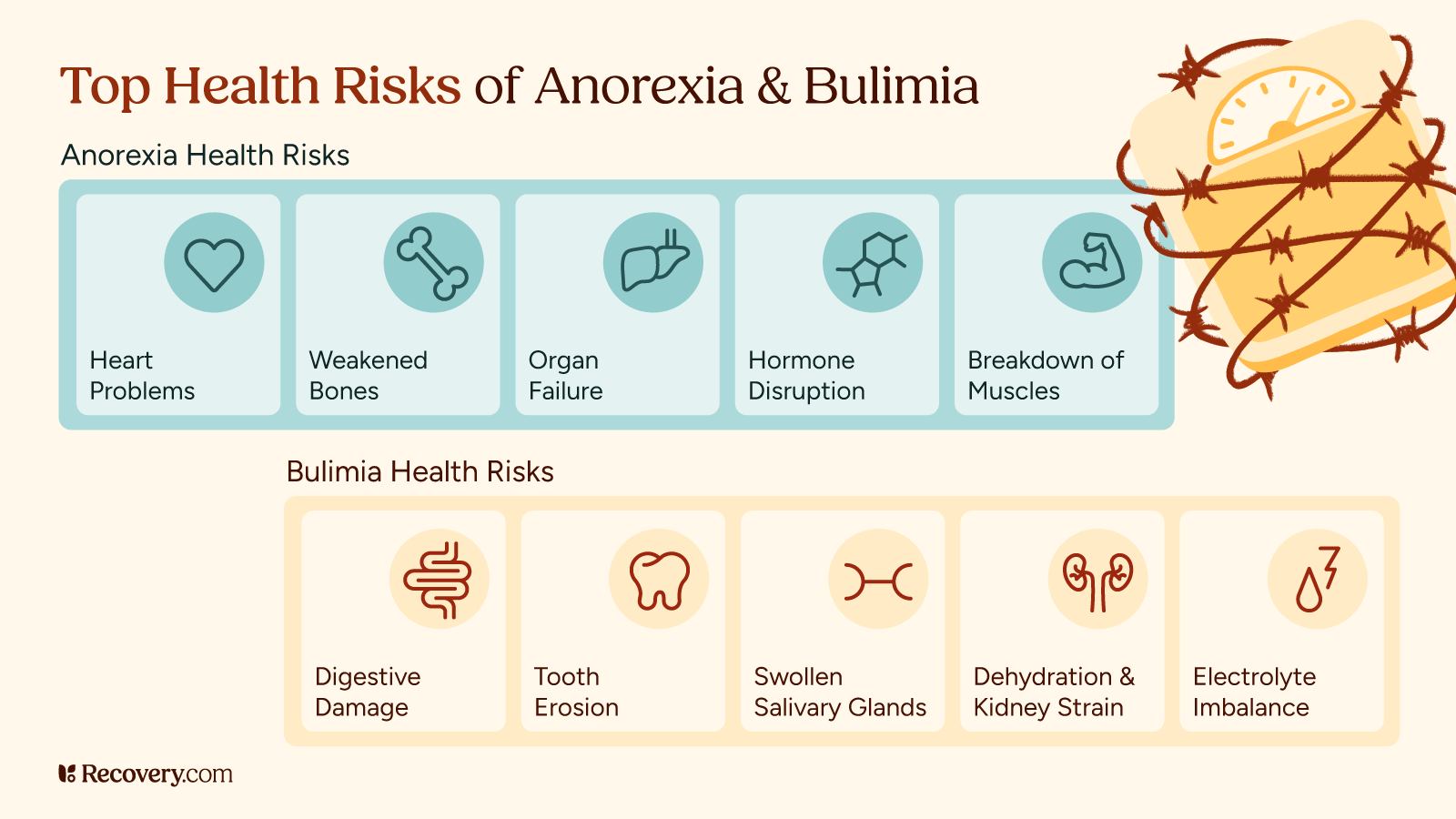

Anorexia and bulimia both cause serious health problems, but in different ways.

Health Risks of Anorexia

Anorexia has the highest death rate of any mental illness, with risks coming mainly from malnutrition that affects every system in the body.12 Severe malnutrition can cause:

- Heart problems.

- Bone loss.

- Muscle wasting.

- Hormone imbalances.

- In the worst cases, organ failure.

Health Risks of Bulimia

Bulimia’s health risks come mainly from purging behaviors. Frequent vomiting can cause:13

- Irregular heartbeat from electrolyte imbalance.

- Cardiac arrest in severe cases.

- Damage to the digestive system.

- Tooth erosion.

- Swollen salivary glands.

Overusing laxatives or diet pills can lead to:

- Laxative dependence.

- Chronic digestive problems.

Hormonal Imbalance

Both disorders can affect fertility and hormones. In anorexia, periods often stop due to low body weight and fat percentage.14 While people with bulimia may continue having periods, hormone disruptions can still happen, which can affect their fertility and bone health.

Long-Term Problems

Long-term problems differ somewhat between these two conditions. With anorexia, long-term malnutrition can lead to:15

- Permanent bone density loss and an increased risk of fractures.

- Heart complications (bradycardia, arrhythmias, hypotension).

- Brain changes and cognitive impairment.

- Reproductive issues.

- Pregnancy complications.

- Gastrointestinal problems.

- Weakened immune function.

- Electrolyte imbalances that affect multiple organ systems.

- Increased overall mortality risk if left untreated.

Bulimia’s long-term effects include:16

- Chronic digestive problems.

- Dental complications (tooth decay, gum disease).

- Higher risk of esophageal cancer from repeated exposure to stomach acid.

- Osteoporosis due to nutritional deficiencies.

- Menstrual irregularities and reproductive problems.

- High cholesterol.

- Increased risk of diabetes.

- Heart irregularities and arrhythmias.

- Severe dehydration and electrolyte imbalances.

- Anemia.

While some health issues like amenorrhea, acute dehydration, and certain heart problems may go away after recovery, others like osteoporosis, reproductive issues, diabetes risk, and cholesterol problems may need ongoing medical monitoring.

Medical Emergencies

If you experience fainting, chest pain, difficulty breathing, seizures, or blood in vomit, please seek emergency medical care immediately—these are not symptoms to ignore or push through. These signs indicate your body is in serious distress and requires urgent professional attention. We know reaching out to someone about an eating disorder can feel overwhelming, but regular medical supervision is absolutely essential to monitor and address these potentially life-threatening complications.

What approaches are most effective for families supporting a loved one in the early stages of eating disorder recovery?

It is important for families of loved ones in eating disorder recovery to be gentle and firm simultaneously. Be gentle in a way that validates one’s feelings, but be firm in not accommodating anxiety around eating. What would that look like? One may say to their loved one, ‘I can understand how you feel, and it is important to follow your therapist’s recommendations and eat to nourish your body.’ Using the word ‘and’ instead of ‘but’ validates both aspects of one’s experience and their long-term goal.

Jennifer Chicoine, MA, LCPC, CCTP | Peaceful Healing Counseling Services

Treatment Approaches

There’s real hope for recovery from eating disorders—both anorexia and bulimia respond well to proper treatment, and many people go on to live healthy, fulfilling lives free from these struggles.17 While the journey has its challenges, effective treatments exist and are continually improving.

Treatment approaches for anorexia and bulimia share some similarities, but also have important differences tailored to each condition. For someone with anorexia, especially when their weight has become dangerously low, the first priority is ensuring medical stability and safety. This compassionate healthcare might include time in a hospital orinpatient treatment center where a team of medical professionals can help restore weight in a gentle, supportive way.

With bulimia, treatment typically focuses on breaking the cycles of binging and purging and rebuilding a healthier relationship with food. Outpatient therapy is often the starting point, but some people might need additional medical support to address health complications.

People can and do recover, and build lifelong healthy relationships with food.6 As Aas says,

You deserve to eat, you deserve to recover from an eating disorder, you are worthy of love, you are worthy of acceptance—mainly from yourself.

Learn more about evidence-based approaches that can transform your journey to recovery in our guide to finding treatment for eating disorders.

Therapy

Both conditions benefit from psychotherapy, but the approaches might differ. For people with anorexia, family-based treatment (FBT) shows strong results, especially for adolescents.18 This approach empowers their family members to take an active role in their recovery.

For bulimia, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is often the go-to treatment. It helps people identify unhelpful thought patterns, develop regular eating habits, and learn healthier ways to cope with their feelings.

Both conditions can also benefit from dialectical behavior therapy (DBT), which teaches skills for managing emotions and relationships.19

Nutritional Counseling

Nutritional counseling plays a major role in treating both disorders, though the goals differ. For anorexia, the focus is on gradually increasing food intake and expanding variety. For bulimia, establishing regular eating patterns and challenging food rules is key to breaking the binge-purge cycle.

Medication

Medication has a more established role in bulimia treatment, with certain antidepressants showing effectiveness in reducing binge-purge behaviors.20 For anorexia, medication is less commonly the primary treatment but may help with co-occurring conditions like anxiety or depression.

Compassionate, Comprehensive Recovery and Support for Eating Disorders

Healing from an eating disorder takes both professional guidance and loving support. The journey looks different for everyone—people with anorexia may start with rebuilding their physical health, while people with bulimia may focus on establishing gentle routines.

When friends and family create spaces free of food judgment, recovery flourishes. And with compassionate professionals by your side, even setbacks become stepping stones.

Many people with these conditions find their way to complete recovery. Your struggle isn’t a personal failure—it’s a health condition that responds to care. If you’re suffering, find an eating disorder treatment program that meets your needs and reach out to a specialist today.

You deserve support, and healing is within reach.

FAQs

-

1. ‘Eating Disorder Statistics’. National Eating Disorders Association, https://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/statistics/. Accessed 28 Apr. 2025.

-

2. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. DSM-5 Changes: Implications for Child Serious Emotional Disturbance [Internet]. Rockville (MD): Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US); 2016 Jun. Table 19, DSM-IV to DSM-5 Anorexia Nervosa Comparison. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519712/table/ch3.t15/

-

3. ‘Symptoms - Anorexia Nervosa’. Nhs.Uk, 11 Feb. 2021, https://www.nhs.uk/mental-health/conditions/anorexia/symptoms/

-

4. ‘Bulimia Nervosa’. National Eating Disorders Association, https://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/bulimia-nervosa/. Accessed 28 Apr. 2025.

-

5. ‘Anorexia Nervosa’. National Eating Disorders Association, https://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/anorexia-nervosa/. Accessed 28 Apr. 2025.

-

6. "Let Go Of SHAME, GUILT And Feeling UNWORTHY // Eating Disorder Recovery." Follow the Intuition. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k0wxWWVW3zk

-

7. Pritts, Sarah D., and Jeffrey Susman. ‘Diagnosis of Eating Disorders in Primary Care’. American Family Physician, vol. 67, no. 2, Jan. 2003, pp. 297–304. www.aafp.org, https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2003/0115/p297.html.

-

8. Mallaram GK, Sharma P, Kattula D, Singh S, Pavuluru P. Body image perception, eating disorder behavior, self-esteem and quality of life: a cross-sectional study among female medical students. J Eat Disord. 2023 Dec 15;11(1):225. doi: 10.1186/s40337-023-00945-2. PMID: 38102717; PMCID: PMC10724937.

-

9. Barakat S, McLean SA, Bryant E, Le A, Marks P; National Eating Disorder Research Consortium; Touyz S, Maguire S. Risk factors for eating disorders: findings from a rapid review. J Eat Disord. 2023 Jan 17;11(1):8. doi: 10.1186/s40337-022-00717-4. PMID: 36650572; PMCID: PMC9847054.

-

10. Eddy KT, Dorer DJ, Franko DL, Tahilani K, Thompson-Brenner H, Herzog DB. Diagnostic crossover in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: implications for DSM-V. Am J Psychiatry. 2008 Feb;165(2):245-50. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07060951. Epub 2008 Jan 15. PMID: 18198267; PMCID: PMC3684068.

-

11. ‘Disordered Eating: Psychological Health & Stress Reduction: Health Answers: Student Health Center: Indiana University Bloomington’. Student Health Center, https://healthcenter.indiana.edu/health-answers/psychological-stress/disordered-eating.html. Accessed 28 Apr. 2025.

-

12. Auger N, Potter BJ, Ukah UV, Low N, Israël M, Steiger H, Healy-Profitós J, Paradis G. Anorexia nervosa and the long-term risk of mortality in women. World Psychiatry. 2021 Oct;20(3):448-449. doi: 10.1002/wps.20904. PMID: 34505367; PMCID: PMC8429328.

-

13. Sagar, Ashwini. ‘Long Term Health Risks Due to Impaired Nutrition in Women with a Past History of Bulimia Nervosa’. Nutrition Noteworthy, vol. 7, no. 1, 2005. escholarship.org, https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6vt2k42t.

-

14. Surbey, Michele K. ‘Anorexia Nervosa, Amenorrhea, and Adaptation’. Ethology and Sociobiology, vol. 8, Jan. 1987, pp. 47–61. ScienceDirect, https://doi.org/10.1016/0162-3095(87)90018-5.

-

15. Meczekalski, Blazej, et al. ‘Long-Term Consequences of Anorexia Nervosa’. Maturitas, vol. 75, no. 3, July 2013, pp. 215–20. ScienceDirect, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2013.04.014.

-

16. Sagar, Ashwini. ‘Long Term Health Risks Due to Impaired Nutrition in Women with a Past History of Bulimia Nervosa’. Nutrition Noteworthy, vol. 7, no. 1, 2005. escholarship.org, https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6vt2k42t.

-

17. ‘Disordered Eating: Psychological Health & Stress Reduction: Health Answers: Student Health Center: Indiana University Bloomington’. Student Health Center, https://healthcenter.indiana.edu/health-answers/psychological-stress/disordered-eating.html. Accessed 28 Apr. 2025.

-

18. ‘Family-Based Treatment for Eating Disorders’. Child Mind Institute, https://childmind.org/article/family-based-treatment-for-eating-disorders/. Accessed 28 Apr. 2025.

-

19. Murphy R, Straebler S, Cooper Z, Fairburn CG. Cognitive behavioral therapy for eating disorders. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2010 Sep;33(3):611-27. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2010.04.004. PMID: 20599136; PMCID: PMC2928448.

-

20. Costandache GI, Munteanu O, Salaru A, Oroian B, Cozmin M. An overview of the treatment of eating disorders in adults and adolescents: pharmacology and psychotherapy. Postep Psychiatr Neurol. 2023 Mar;32(1):40-48. doi: 10.5114/ppn.2023.127237. Epub 2023 May 8. PMID: 37287736; PMCID: PMC10243293.

Our Promise

How Is Recovery.com Different?

We believe everyone deserves access to accurate, unbiased information about mental health and recovery. That’s why we have a comprehensive set of treatment providers and don't charge for inclusion. Any center that meets our criteria can list for free. We do not and have never accepted fees for referring someone to a particular center. Providers who advertise with us must be verified by our Research Team and we clearly mark their status as advertisers.

Our goal is to help you choose the best path for your recovery. That begins with information you can trust.